Who were UCL's first Chinese students?

Since the 19th century, Chinese students have formed a vital part of the UCL community. But who were the first Chinese students? Professor Georgina Brewis and Dr Jenny Bond shed light

One of the most striking changes to UCL’s student body in the past five years is the growing number of Chinese students, with over 15,000 from mainland China enrolled at UCL in 2024 and more than 21,000 joining the alumni community since 2014. Yet Chinese students have a much longer history of coming to study in London.

Many Chinese students and alumni have been interested in their predecessors, but, with little written information available on these trailblazers, have been unable to learn more.

A key goal of our project Generation UCL: 200 Years of Student Life in London is to reexamine the diversity of students in the past. With this in mind, we decided to research and write the first academic article exploring the lives of Chinese students at British universities and colleges in the pre-Communist era.

This is a challenging task. There is no comprehensive register of UCL students, information on geographical origins was collated only from the early twentieth century, and data on ethnicity was not collected until the 1990s. Despite the challenges, here we present some of our findings, together with research undertaken on Chinese students at UCL.

A new chapter

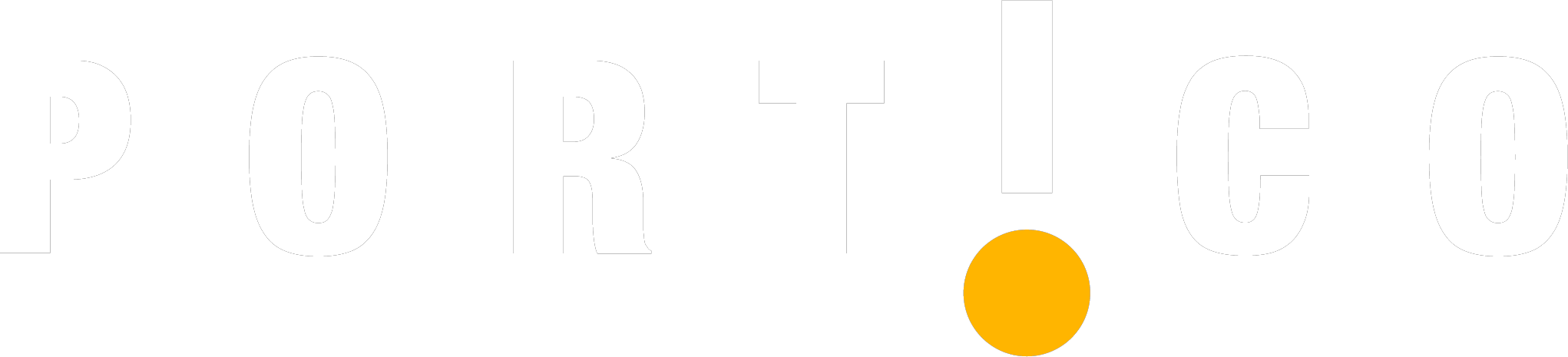

Chinese students started to come to the UK in the second half of the nineteenth century, when they were usually sponsored either by Christian missionary societies or the Chinese government. It was not until the very last years of the Qing dynasty, around 1908-1911, that the number of students started to increase substantially. Patterns of student mobility reflected British influence in China, with large numbers of students coming from what was then known as Canton (Guangdong), and port cities such as Shanghai and Tianjin.

These first students sought technical and professional qualifications in Engineering, Mining and Medicine. The earliest students we’ve so far been able to find at UCL were two who arrived from Beijing to study Engineering in 1899: T. S. Po-Jui and Kuo Tung. The students were sponsored by the Qing government, which we know because both student forms list their guardian as the “Chinese Minister, Chinese Legation” (as China’s diplomatic mission in London was known before it was upgraded to an Embassy in 1935).

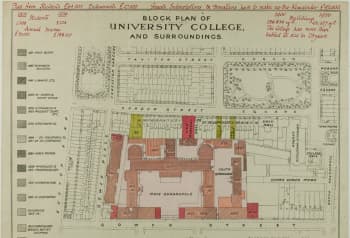

Po-Jui and Kuo Tung both completed a full three-year programme, taking a range of courses in Physics, Graphics, Surveying, Architecture, Civil and Municipal Engineering, but do not seem to have taken a degree. Po-Jui stayed for a time at the Chinese Legation in Portland Place, but in the 1901 census he is listed as living in Oakley Square in the house of John Savel, a man listed as a private tutor by profession, and recorded as Po-Jui’s father-in-law. Was this a census enumerator’s mistake or had Po-Jui married a girl he met in London? Such mixed marriages between students and middle-class British women were very rare but not unheard of, and this warrants further research.

A blossoming community

In 1901 the Chinese Legation supported a further two Engineering students, T. C. Linpao and K. F. Enhou. Some of the earliest privately funded students at UCL include Chenping Hu, who came from Shanghai to study French in 1905, and Chen-Hu Shen, who enrolled on a History course in 1904 – but sadly we know little about these beyond these bare facts.

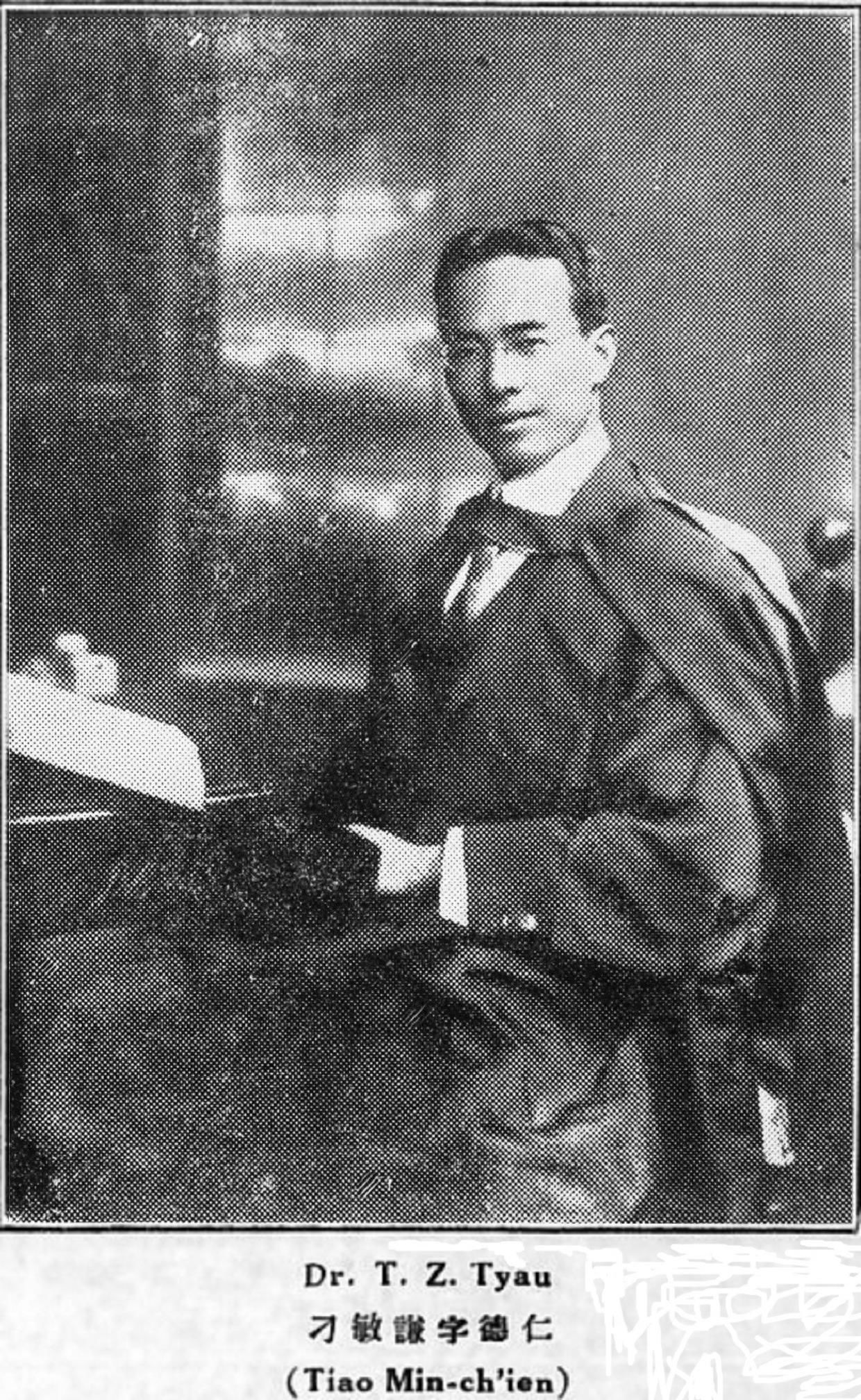

We know much more about two slightly later students F. T. Cheng (Zheng Tianxi 鄭天錫, 1884-1970) and M.T. Z. Tyau (Diao Minqian 刁敏謙, 1888-1970) who were law students at UCL in the years just before and during the First World War. Interestingly, in 1916 Cheng beat Tyau by a matter of months to be the first Chinese person to complete a University of London doctorate (LLB), and that year they shared the prestigious Quain Prize in International Law.

Cheng wrote about his experiences at UCL in his autobiography, describing his lodgings in Gower Street, where for two guineas a week he had bacon and eggs for breakfast, roast beef for lunch and "often half a lobster and salad" for dinner.[i] As his savings ran out, Cheng moved to cheaper lodgings in Highbury before ending up in the north London suburb of Wood Green. Tyau, who went on to be an academic and writer, also wrote about Chinese students in the UK, in his book London through Chinese Eyes.[ii]

Both Cheng and Tyau witnessed hundreds of new Chinese students arrive during their long sojourns in London, whom they supported with advice and academic coaching. In 1910, when UCL started publishing tables showing the geographical distribution of students, 15 students were listed as coming from China and one from Hong Kong. In the 1920s and 1930s there were between 30 and 35 each year who were marked as originating from China. In 1930 the total number of Chinese students at British universities and colleges was 450, compared to around 2,500 studying in Japan, 2,000 in the USA, 1,500 in France and 300 in Germany.[iii]

Around half of those described as “Chinese students” came from the Chinese mainland and the other half from British colonies including Hong Kong, Burma (Myanmar), British Malaya, and the British West Indies. By the 1930s, larger numbers were studying social, economic and political sciences and there were proportionally more privately funded students than those sponsored by governments. Most students were men, with only about ten per cent women, a pattern reflected at UCL.

F.T. Cheng (Zheng Tianxi 鄭天錫) 1884-1970

F.T. Cheng (Zheng Tianxi 鄭天錫) 1884-1970

M.T. Z. Tyau (Diao Minqian 刁敏謙) 1888-1970

M.T. Z. Tyau (Diao Minqian 刁敏謙) 1888-1970

Lucy See sent this photo of herself with her baby to her friends at College Hall after her marriage. Image: Reproduced with permission of Senate House Library

Lucy See sent this photo of herself with her baby to her friends at College Hall after her marriage. Image: Reproduced with permission of Senate House Library

Chinese students in British universities and colleges formed their own students’ unions in university towns including Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh and Manchester. These associations offered fellowship and opportunities to socialise.

There was a large and active London Chinese Students’ Union comprising students from different colleges and medical schools, which organised a regular debating club at Student Movement House alongside an extensive social programme. Many of the early students identified as Christian and before the First World War, the most important national association was the Chinese Students’ Christian Union, founded in 1908.

In 1907, a secular Chinese Students’ Union emerged out of two associations that had been meeting since around 1904. By 1916 this was known as the Central Union of Chinese Students, and it became the most important channel for Chinese student associational life, with two publications: The Chinese Student in English as well Liuying xuebao (留英學報) in Chinese. The Central Union held an annual dinner in October to mark the anniversary of the Republic and a week-long conference featuring talks, sports and social activities.

UCL law student Lucy See from Singapore helped organise the social events at the 1926 summer conference in Birmingham which included a fancy-dress party and a concert at which Lucy played guitar. These groups sought to connect Chinese students with one another and to promote students’ welfare. But they helped students to act as cultural ambassadors by “interpreting China to the West” in an attempt to counter misinformation and lurid, racist depictions of Chinese people in popular literature and the cinema.[iv]

London living

By the 1930s there were several hundred Chinese students in London, which at that point attracted over half of all Chinese students who came to the UK. Many lived in lodgings in Bloomsbury and by the 1920s this Chinese presence was so noticeable that it was referred to in ‘Bloomsbury Blues’, a song published in the UCL Student’s Songbook, to be sung to the tune of the popular song ‘Limehouse Blues’, about London’s first ‘Chinatown’.

London exerted a strong pull on many Chinese students. Tyau noted in London Through Chinese Eyes how as a child he had felt that visiting London would be the "height of human happiness" and "an earthly Paradise". However, many also experienced disillusionment and loneliness on arriving in London. Arriving in 1934, and moving into a boarding house near Russell Square run by a “greedy and miserly couple”, Yang Xianyi (楊憲益 1915-2009) described London as “polluted”, “shabby” and “old-fashioned”.[v]

The earliest students had had few opportunities to eat Chinese food for they rarely visited London’s original ‘Chinatown’, which had grown up since the 1880s in Limehouse. By the 1920s a growing number of Chinese restaurants and businesses were opening in the West End, close to UCL, and were largely sustained by the student trade. In 1928, the manager of one of these, the Canton Restaurant, allowed the Central Union of Chinese Students to use a room as its headquarters. The Chinese Student carried numerous advertisements for The Canton, The Nanking and The Shanghai.

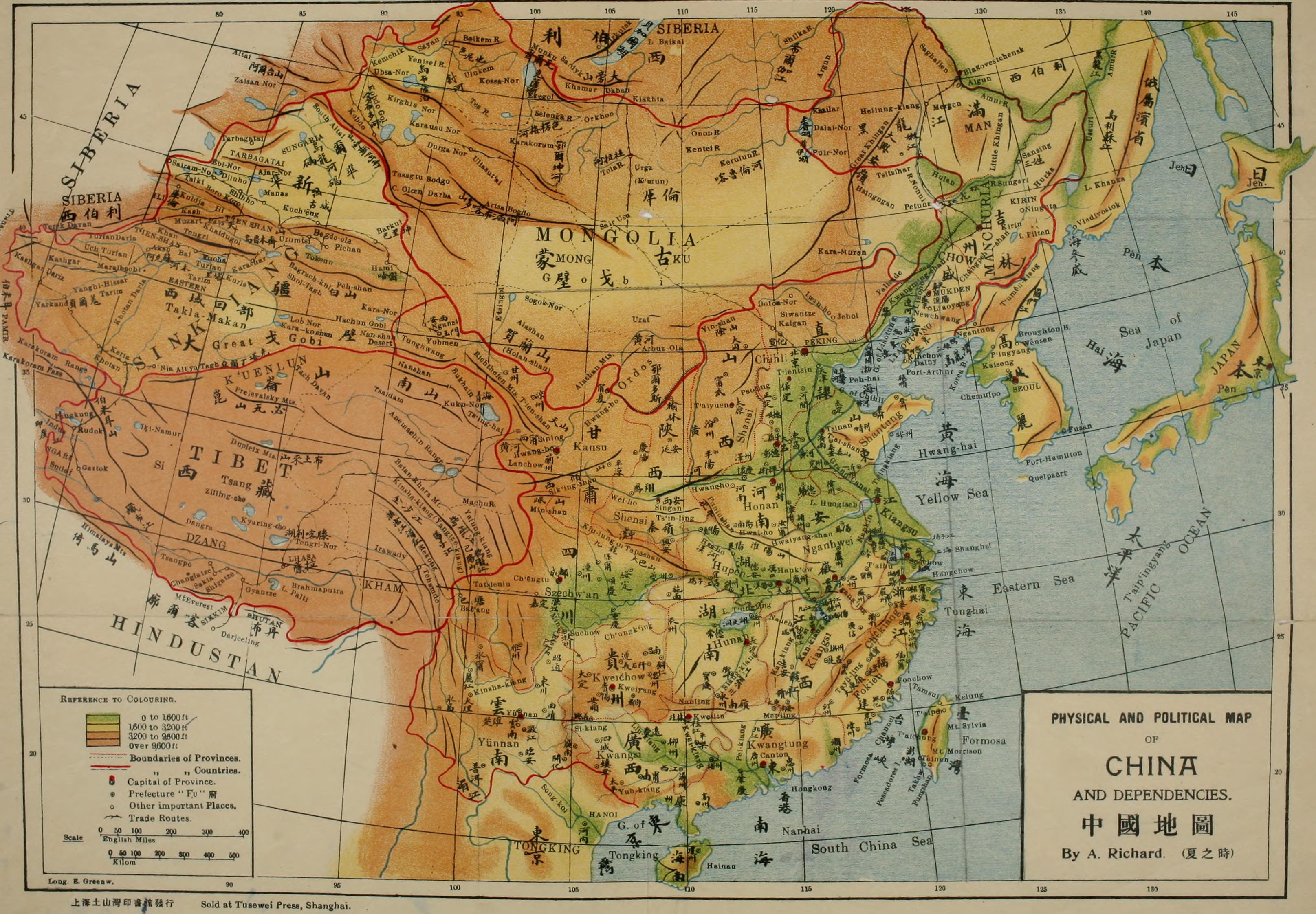

In 1933, the Central Union of Chinese Students opened a club and hostel for Chinese students called China House at 91 Gower Street, just across the road from the Indian Student Hostel (on the site of what is now UCL’s Darwin Building). Funded by the Universities China Committee in London, China House was hailed as a "landmark of Sino-British friendship" with a library, refreshment lounge, games room and committee room, and a few bedrooms available to students arriving in London without lodgings lined up. It was decorated in a supposedly "harmonious blending of Chinese and European designs and colour" and provided shared headquarters for several China organisations.[vi] By the end of 1933, hundreds of students had joined and found it to be much-needed venue for inter-cultural exchange, including between overseas Chinese and students from the Chinese mainland.

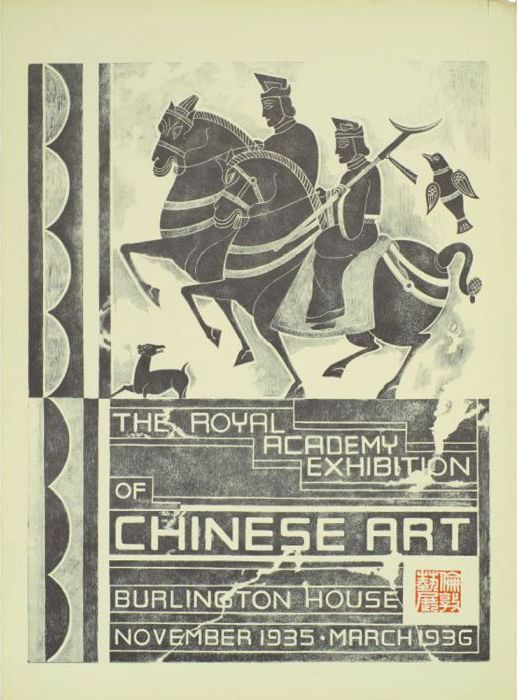

In 1935 F. T. Cheng was sent back to London by the Republican Government as Special Commissioner accompanying artworks for the Exhibition of Chinese Art at the Royal Academy of Arts, Burlington House. Attended by King George V and Queen Mary in their last ever public engagement before the King’s death in January 1936, this was the blockbuster art show of the inter-war period.

Hundreds of Chinese students visited the exhibition on special-price tickets and appreciated the positive press coverage for China that the exhibition generated. In October 1935, Cheng was the keynote speaker at the annual dinner of the Central Union of Chinese Students, when 180 guests packed Lisbeth Hall in Soho Square to mark the 24th anniversary of the establishment of the Republic of China. The students, in their ties and blazers of blue, red and white (reflecting both the Republic of China flag and the Union flag), raised toasts to both ‘the King’ (of the United Kingdom) and ‘the Republic’ (of China).

This dinner-dance marked a high point of Chinese student culture in London before the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, which seriously affected the student population. Many students returned home immediately, while passport restrictions and travel problems stopped the flow of new students. From a mid-1930s peak of many hundreds, by 1943 there were just 50 Chinese students left in British universities and colleges.[vii]

The connection with UCL was not over for Cheng, however, who was made a Fellow of UCL in 1938. After a serving as a Judge at the Permanent Court of International Justice in The Hague, Cheng returned to London as the last Ambassador of the Republic of China 1946-1950. A law prize in his name was established at UCL in 1984.

Following in Cheng's footsteps, his son Bin Cheng 鄭斌 (1921-2019) studied at UCL for a PhD and LL.D. An expert in air and space law, Bin Cheng was a Law lecturer at UCL from the 1950s and served as Dean of UCL Laws in the 1970s.

While there is more to learn about UCL's earliest Chinese students, what's clear is that the university's Chinese community has gone from strength to strength. While it remains to be seen what UCL's third century will bring, it is evident from almost 200 years of history that a diverse community, including Chinese students, will be at the heart.

Professor Georgina Brewis is Professor of Social History at IOE, UCL’s Faculty of Education and Society and leads Generation UCL: Two Hundred Years of Student Life in London.

Dr Jenny Bond is a Lecturer at IOE, UCL’s Faculty of Education and Society, where she researches the history of modern China.

Acknowledgements: with thanks to Robert Winckworth from UCL Special Collections for his help with student record files and student research fellow Zhiruo He for transcribing data on student numbers

Poster for The International Exhibition of Chinese Art held at the Royal Academy in 1935-6.

Poster for The International Exhibition of Chinese Art held at the Royal Academy in 1935-6.

Professor Bin Cheng at UCL with Zara Brawley, winner of the Cheng Tien-Hsi Prize for Public International Law, in 2011

Professor Bin Cheng at UCL with Zara Brawley, winner of the Cheng Tien-Hsi Prize for Public International Law, in 2011

The 'Generation UCL: 200 Years of Student Life in London' exhibition is a look at two centuries of student life at UCL and in London, mounted in the run-up to UCL’s bicentenary celebrations in 2026.

Learn more about UCL's first Chinese students in the Modern British History article 'Ambassadors of cultural appreciation': the social, political and associational life of Chinese students in Britain, 1908-37

[i] F.T. Cheng, East and West: Episodes in a Sixty Years Journey (London: Hutchinson and Co, 1951).

[ii] M.T.Z. Tyau, London through Chinese Eyes (London: Swarthmore Press, 1920).

[iii] S. Sze, ‘Chinese students in Great Britain’ Asiatic Review 27, no. 90 (April 1931): 311–320.

[iv] ‘Foreword’, Chinese Student (July 1926), 1.

[v] Y. Xianyi, White Tiger: An Autobiography of Yang Xianyi (Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2002), 37.

[vi] ‘China House: Formal opening of students' home in London’, South China Morning Post, 18 Feb. 1933.

[vii]China Today: Resistance and Reconstruction (London: Central Union of Chinese Students, 1943).

Portico magazine features stories for and from the UCL community. If you have a story to tell or feedback to share, contact advancement@ucl.ac.uk

Editor: Lauren Cain

Editorial team: Ray Antwi, Laili Kwok, Harry Latter, Bryony Merritt, Lucy Morrish, Alex Norton