Shelf life

UCL’s libraries and collections are a cornerstone of the student and academic experience. Here, the UCL Library Services team tell us more about the incredible items in their collections and archives, including George Orwell’s love letters and Mary, Queen of Scots’ hair – and reveal which buildings are reputedly haunted

There are 17 library sites across UCL’s campus, as well as the Special Collections Reading Room and offsite storage. Between them, they house around two million print books across 105km of shelves – roughly the same length as London Underground’s newly opened Elizabeth Line. In the 2021/22 academic year, we ordered 7,184 print books, as well as providing access to more than a million ebooks, from which 4,580,885 chapters were downloaded. The most heavily used was Management Accounting for Decision Makers 10th edition, by Peter Atrill and Eddie McLaney, which was used 8,550 times.

The most overdue book

Last year, we were sent a copy of a long-overdue book, a play called Querolus, alongside an anonymous letter that read: “Dear Librarian, I fear this book is some 50 years overdue! Please don’t just throw it out now that I’ve taken the time and trouble to return it. It must be an ‘antique’ by now.”

The book’s original due date was in summer 1974, meaning that it would have accrued overdue fines of £1,254 at 10p per day (which we waived). While we encourage customers to return their books on time so that other users can read them, automatic renewals have also been in place since March 2021.

Beyond the libraries’ open shelves, UCL Special Collections has approximately 400 archive and rare book collections, some of which are extremely large. For example, the archive of the Brougham family (notably Henry Peter Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux, one of the founders of UCL) contains 970 boxes and runs to 164 linear metres, covering all aspects of his work as Lord Chancellor, including the 1832 Reform Act and the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act.

The biggest collection of rare books is the Graves Library, which covers the history of mathematics from the 13th to the 19th centuries and comprises 10,270 items, or 234 metres of shelving. However, the most extensive collection overall, at more than 1,000 boxes is UCL’s own historical archive, which charts the history of UCL from its foundation in 1826 to the present day.

A satirical print from the Brougham family archive

A satirical print from the Brougham family archive

A page of geometric shapes from the Graves Library

A page of geometric shapes from the Graves Library

Everything in Special Collections is in some way unique – archives are created by individuals and organisations and are irreplaceable, as are rare books, which, although there may be other copies of titles, will have annotations or a provenance that make them one of a kind.

In a recent project to digitise 18th-century books for Gale’s Eighteenth-Century Collections Online (ECCO), we identified 59 editions of books that had not previously been recorded – in other words, unique, first-time discoveries. This included works by important female authors, including An Essay on Combustion 1794 by Mrs Elizabeth Fulhame, the first solo woman researcher in chemistry; the prolific Delarivier Manley (sometimes known as Mary de la Rivière); and a four-part Ladies Astronomy from 1738. We also found unique editions by major authors including Swift, Defoe, Pope, Voltaire, Rabelais and Beckford.

The title page of The Ladies Astronomy and Chronology in Four Parts, from 1738

The title page of The Ladies Astronomy and Chronology in Four Parts, from 1738

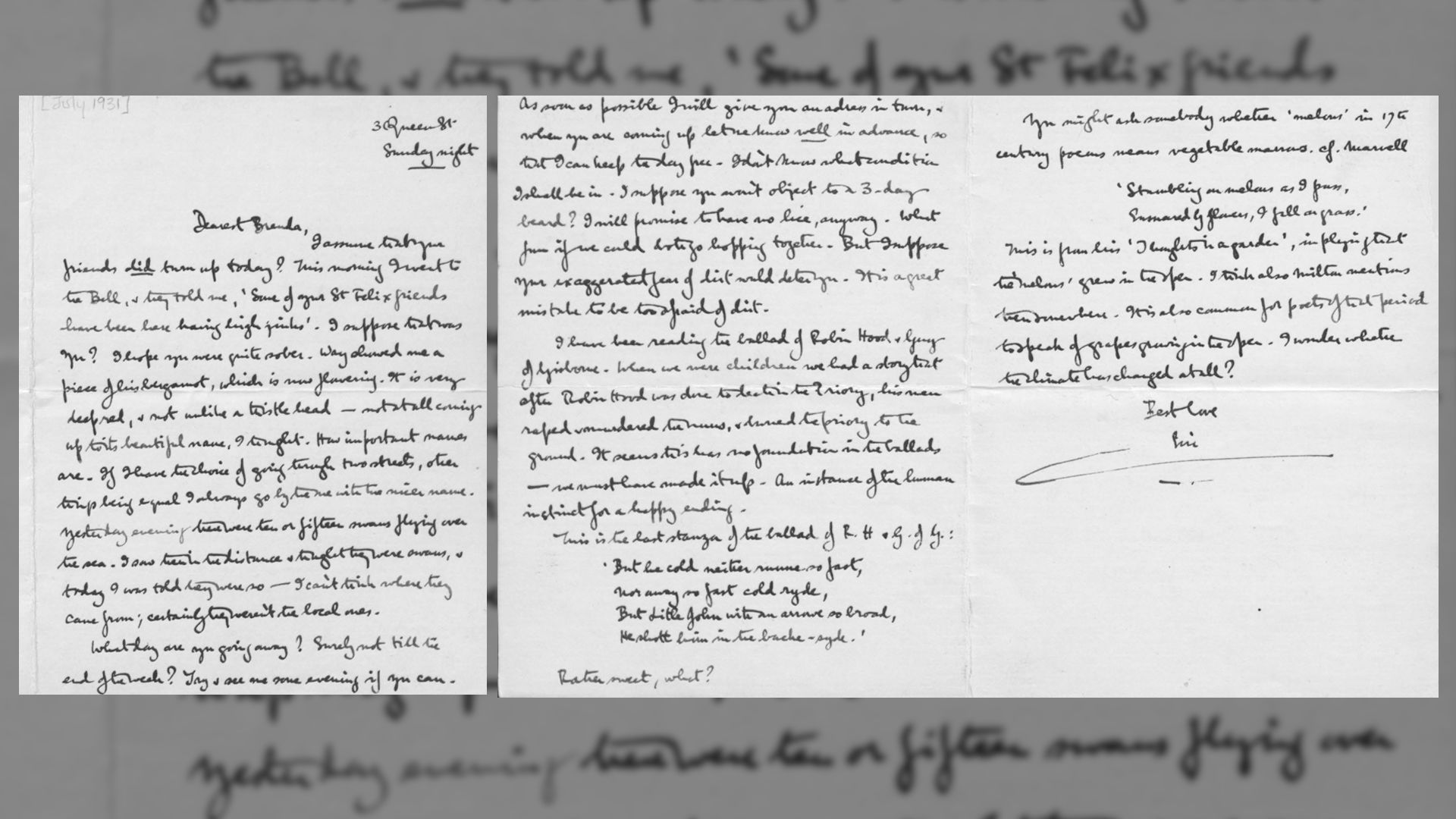

Holdings also include a vast number of letters. A recent donation was a cache from George Orwell to two women, Brenda Salkeld and Eleanor Jaques, during the 1930s and 1940s, which has been added to the Orwell Archive. The letters were kindly donated by Orwell’s son, Richard Blair, and reveal new details about Orwell’s life in the 1930s – including his overlapping romances, his love of ice skating and his struggle to write and publish his first novels. They also show that the two women had a profound importance in his life that lasted long after his romances with them appeared to have ended. The bulk of the letters have not been publicly available until now.

A letter from George Orwell to Brenda Salkeld

A letter from George Orwell to Brenda Salkeld

Recently, Special Collections has worked together with UCL’s Digitisation Suite on several projects, using advanced imaging techniques to answer questions posed by librarians and conservators. Among other things, they have discovered hidden musical notation in a 13th-century manuscript and created an interactive 3D model of an 18th-century book containing an abacus.

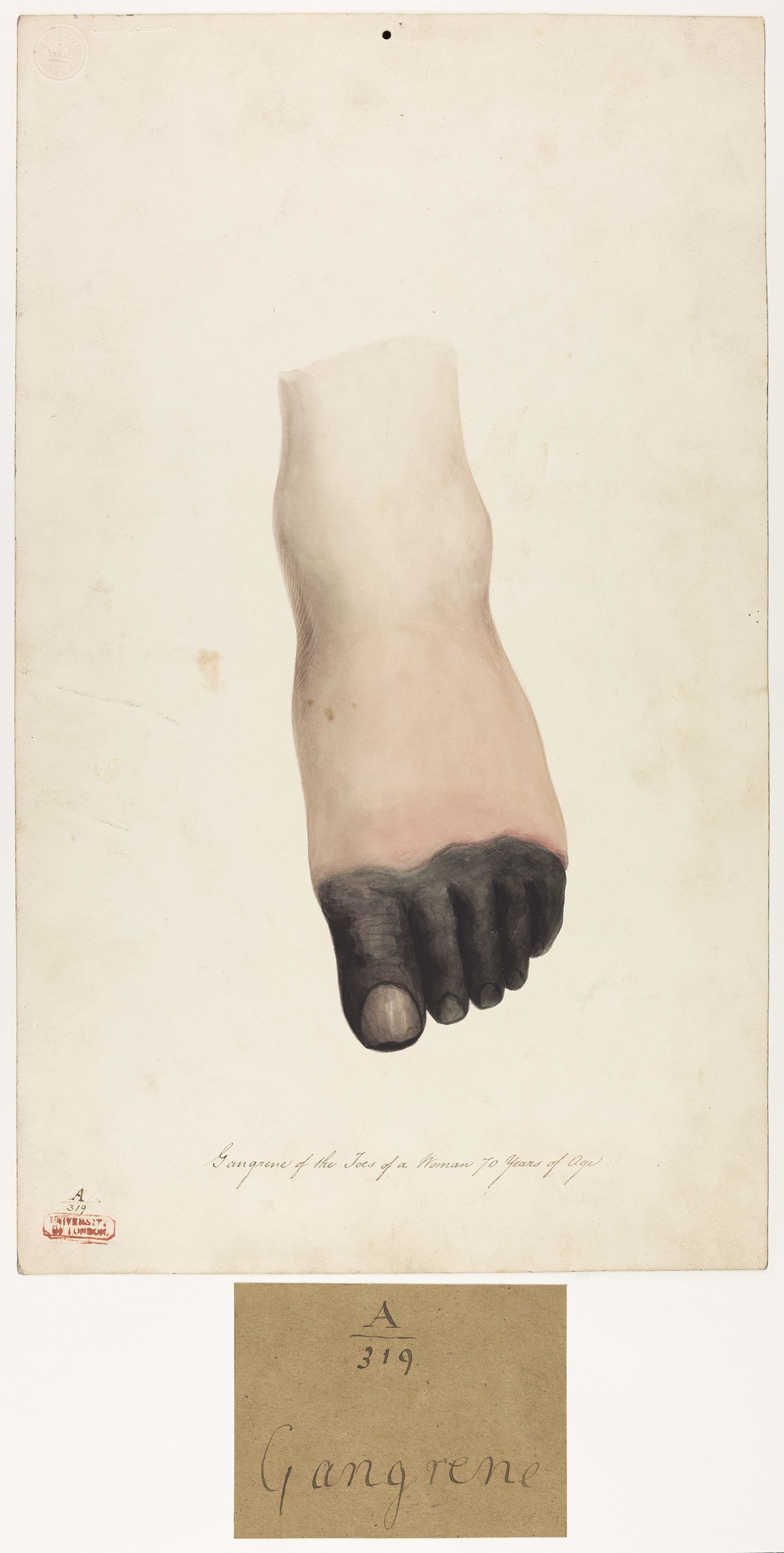

You can see examples of digitised Special Collections material on our Digital Collections page. This includes items from the George Orwell Archive, the Jeremy Bentham Papers and Carswell Illustrations (pathological drawings by Sir Robert Carswell, Professor of Pathological Anatomy, 1831-1840), as well as the history of UCL and selections from our rare-book collections. There are 130,179 digital titles, with 376,381 digital files attached.

The oldest book in the collection

The oldest item we have is not a book but a manuscript fragment of Euripides’ Medea, v.1057-1062, dating from the 4th/5th century CE. This item is part of a larger collection of manuscript fragments that contains pieces of medieval and early modern manuscripts, primarily leaves from liturgical texts including missals, breviaries, psalters, bibles and biblical commentaries, but also including parts of popular medieval textbooks and medieval music, including noted missals and breviaries, antiphonaries and graduals. These fragments were generally used to repair ‘newer’ books and were collected at a later date for the teaching of palaeography (the study of pre-modern manuscripts) at UCL.

Should you dare to dig a little deeper into Special Collections, you will come across some unusual holdings. There is a set of canes and tawses (leather whips), collected as part of the anti-corporal-punishment campaign Society of Teachers Opposed to Physical Punishment (STOPP Archive); macrame owls, lino cuttings and a ‘cursed’ sheep created by children at Eynsham School in Oxfordshire (Baines Archive); and tiny furniture for designing school classrooms (Medd Archive).

A ‘cursed’ sheep created by children at Eynsham School in Oxfordshire (Baines Archives)

A ‘cursed’ sheep created by children at Eynsham School in Oxfordshire (Baines Archives)

There is also a surprising amount of hair in Special Collections. The Helsby family scrapbook is covered in donkey skin; the E S Pearson Papers include hair chains; there are envelopes of Lady Brougham’s hair in the Brougham Papers; and a lock of hair allegedly belonging to Mary, Queen of Scots in the Penrose Papers.

An envelope of Lady Brougham's hair

An envelope of Lady Brougham's hair

Finally, a favourite from the Poetry Store in the Small Press Collections is a poem made up of ‘hundreds and thousands’ (more usually used for cake decorating). You can see the painstaking conservation work undertaken to restore it in the film Homage to G Seurat, A Paper Conservation Challenge.

Volunteering with UCL Library Services

We have volunteers across all aspects of our work, including conservation, cataloguing, events and digitisation. Our volunteers provide huge added value and undertake projects that greatly increase access, such as the recent Liberating the Collections project. We also run school and work-experience placements and free summer schools.

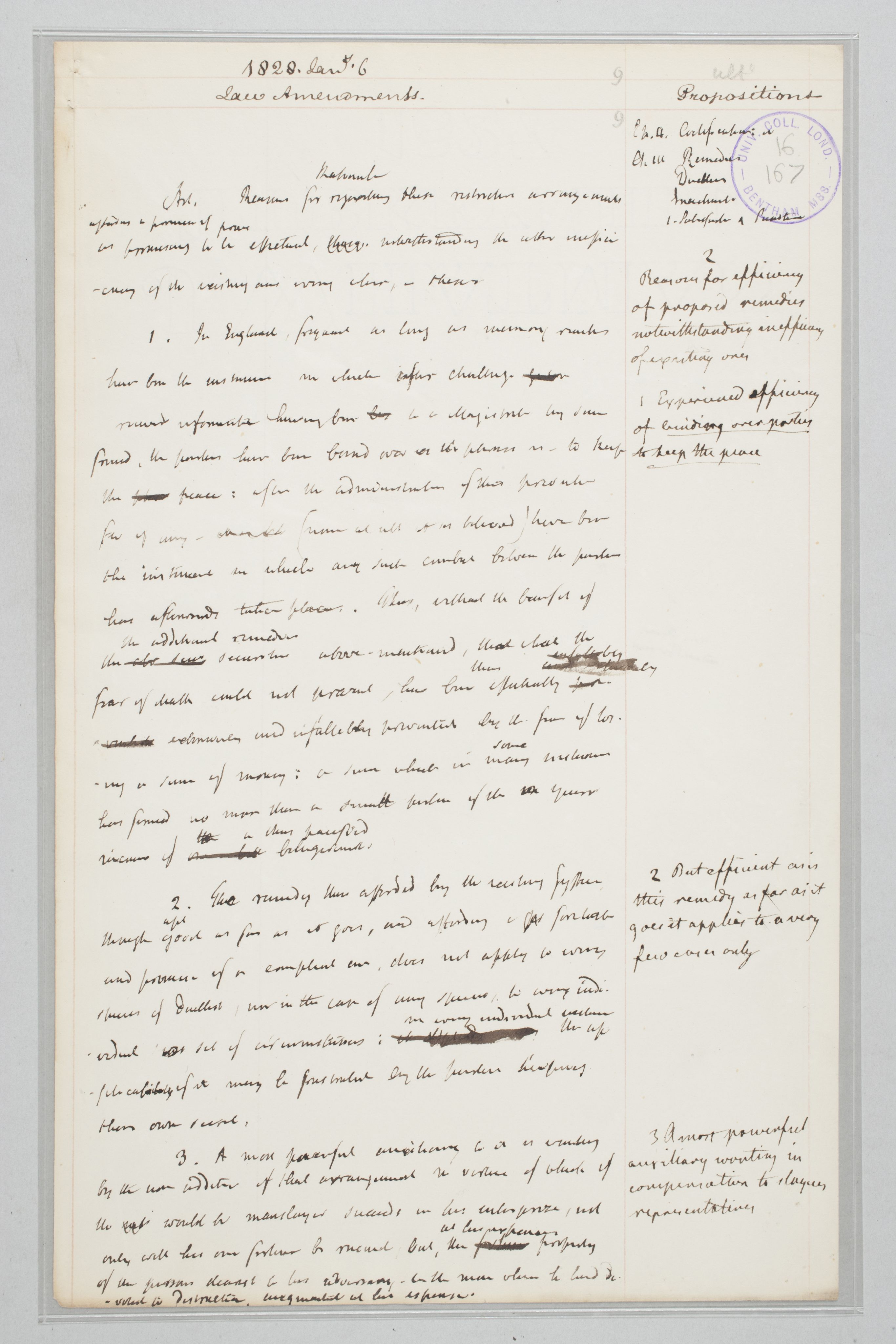

A page of Jeremy Bentham's notes

A page of Jeremy Bentham's notes

An illustration of gangrene of the foot by Sir Robert Carswell

An illustration of gangrene of the foot by Sir Robert Carswell

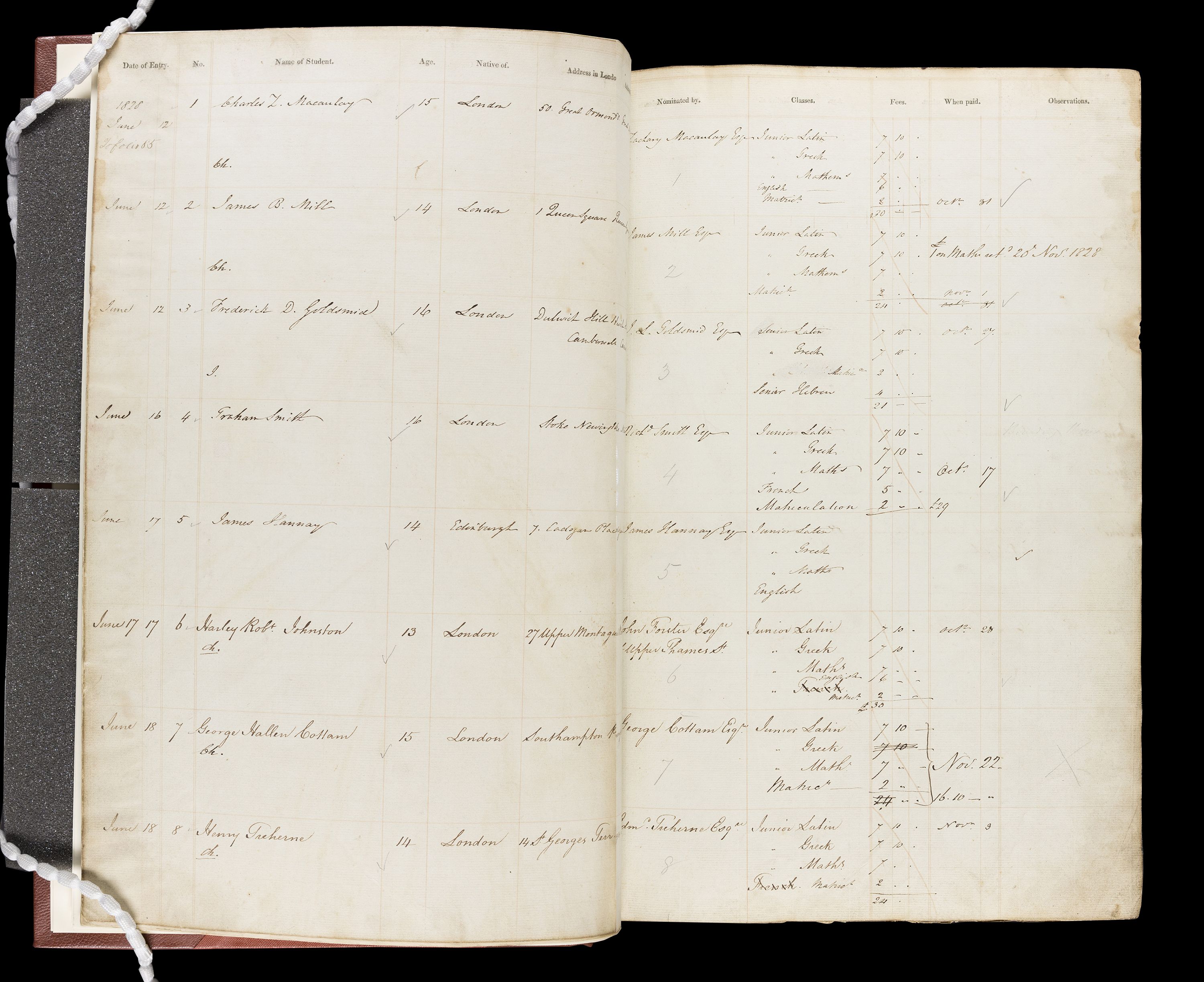

Pages from UCL's first student register in 1828

Pages from UCL's first student register in 1828

UCL’s haunted libraries, reputedly

While we don’t want to put off volunteers, there are stories of hauntings. The UCL Main Library has many ghosts, but the best attested to is the ‘red-haired woman’. Several people, including two members of library staff, have met her. She is described as a young woman with red hair, wearing old clothes, and has been seen walking through the wall in the Jewish & Hebrew section.

The Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital Library in Stanmore is said to be haunted by a Grey Lady. Some claim she is a former nun (the site is built on a former nunnery), while others identify her as Mary Wardell, a Victorian philanthropist who founded a scarlet fever isolation ward on the site in 1883.

However, the scariest ghost stories are connected to Cruciform Hub. According to urban legend, a student was murdered in the tunnels connecting the Cruciform to Arthur Tattersall House, and if you say her name three times, she will appear. While this ghost story is not true, the spooky disused tunnels can still be seen through a window in the Cruciform Hub.

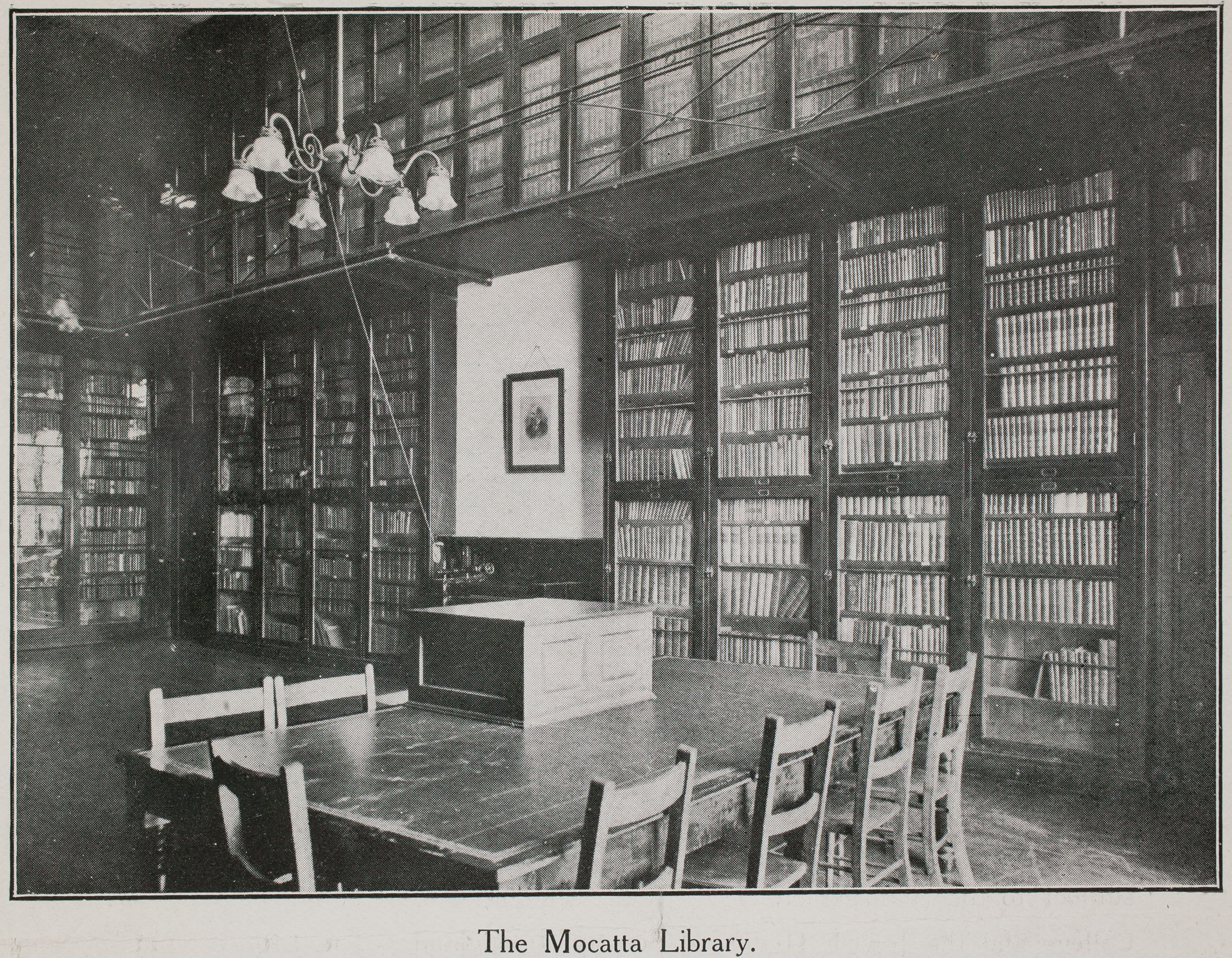

The Old Mocatta Library. The Mocatta collection of Judaica and Hebraica arrived in the Library in 1906. It is now known as Hebrew and Jewish Collections

The Old Mocatta Library. The Mocatta collection of Judaica and Hebraica arrived in the Library in 1906. It is now known as Hebrew and Jewish Collections

The Cruciform Building

The Cruciform Building

Explore the collections of UCL Library Services and find out more about the work of our teams in the Library, Culture, Collections and Open Science Annual Report.

Portico magazine features stories for and from the UCL community. If you have a story to tell or feedback to share, contact advancement@ucl.ac.uk