Breakthroughs

Ideas and impact

Can a new material make construction climate-friendly? How did we gain a 3D view of the heart? Catch up on the latest breakthroughs from UCL’s 11 faculties

Artefacts reveal ancient journeys

UCL Faculty of Social & Historical Sciences

Cutting blades recovered from the rock overhang in Laili. Credit: Dr Ceri Shipton

Cutting blades recovered from the rock overhang in Laili. Credit: Dr Ceri Shipton

The study of ancient sediment, artefacts, and animal remains in East Timor has led to a new understanding of how humans first travelled from Southeast Asia to Australia.

A team led by UCL found a distinct ‘arrival signature’ dating to about 44,000 years ago, indicating there were no humans on the island at a point when settlers had already reached Australia. This means that the first migrants likely used New Guinea – not Timor Island – as a stepping stone to the continent.

“This finding represents a significant change to our understanding of ancient human migration across the Malay Archipelago,” said lead author Dr Ceri Shipton (UCL Institute of Archaeology). “Tracing the ancient journeys of our ancestors is a major challenge, but this new evidence shows that there was a particularly intensive migration across the southern islands soon after 50,000 years ago.”

The research also involved the Australian National University (ANU), Flinders University, and the ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage and was supported by the Australian Research Council.

Read the full story: Excavation indicates a major ancient migration to Timor Island

Concrete’s eco-friendly rival

The Bartlett, UCL's Faculty of the Built Environment

Image of the 0.5x1m C-ELM panels. Credit: Prantar Tamuli

Image of the 0.5x1m C-ELM panels. Credit: Prantar Tamuli

A UCL PhD candidate has developed a new biomaterial, known as a cyanobacterial engineered living material (C-ELM), that could significantly reduce the construction industry's carbon footprint.

C-ELM incorporates living cyanobacteria into translucent panels, absorbing carbon dioxide from the air through photosynthesis, converting it into calcium carbonate and locking the carbon away. Each kilogram of C-ELM can capture and sequester up to 350g of carbon dioxide, while traditional concrete emits 500g.

Prantar Tamuli (UCL Biochemical Engineering), who developed C-ELM under the guidance of research supervisors during his earlier MSc degree in Bio-Integrated Design, said: "My aim by developing the C-ELM material is to transform the act of constructing our future human habitats from the biggest carbon-emitting activity to the largest carbon-sequestering one."

“The promise of this kind of biomaterial is tremendous. If mass produced and widely adopted, it could dramatically reduce the carbon footprint of the construction industry,” said Professor Marcos Cruz (UCL Bartlett School of Architecture and co-director of the Bio-Integrated Design Programme). “We hope to scale up the manufacture of this C-ELM and further optimise its performance to be better suited for use in construction.”

Read the full story: New living building material draws carbon out of the atmosphere

Future proofing for Parkinson’s

UCL Faculty of Brain Sciences

A researcher working with blood vials. Credit: Jacob Wackerhausen on iStock

A researcher working with blood vials. Credit: Jacob Wackerhausen on iStock

Research led by UCL in collaboration with University Medical Center Goettingen has developed a blood test that could predict Parkinson's disease up to seven years before symptoms appear.

Parkinson's is the fastest-growing neurodegenerative disorder, affecting nearly 10 million people globally. Currently, treatment begins after symptoms such as tremors and memory problems arise, but this test uses artificial intelligence (AI) to offer hope for earlier intervention.

In development, the test analysed a panel of eight blood biomarkers altered in Parkinson’s patients using a branch of AI called machine learning, and recorded a diagnostic accuracy of 100%.

“As new therapies become available to treat Parkinson’s, we need to diagnose patients before they have developed the symptoms. We cannot regrow our brain cells and therefore we need to protect those that we have,” said senior author, Professor Kevin Mills (UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health).

This breakthrough could enable earlier drug therapies to slow or prevent the disease by protecting brain cells. Researchers hope to develop a simpler blood spot test and are exploring its use in high-risk populations.

The study was co-funded by Parkinson’s UK and EU Horizon 2020.

Read the full story: Blood test could predict Parkinson’s seven years before symptoms

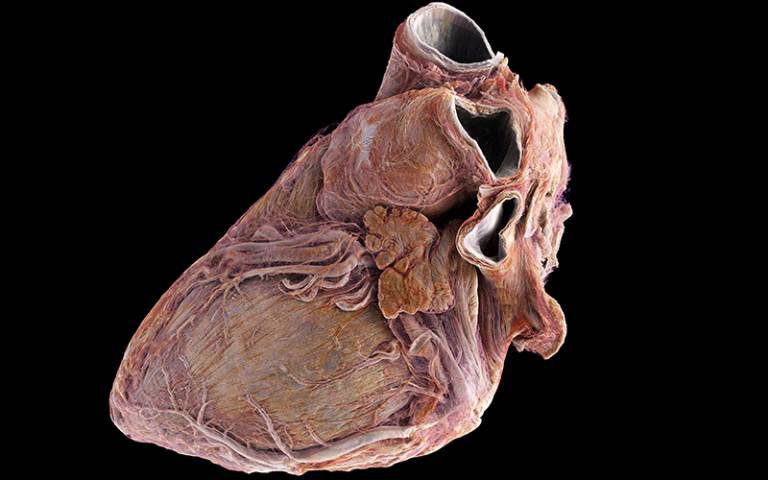

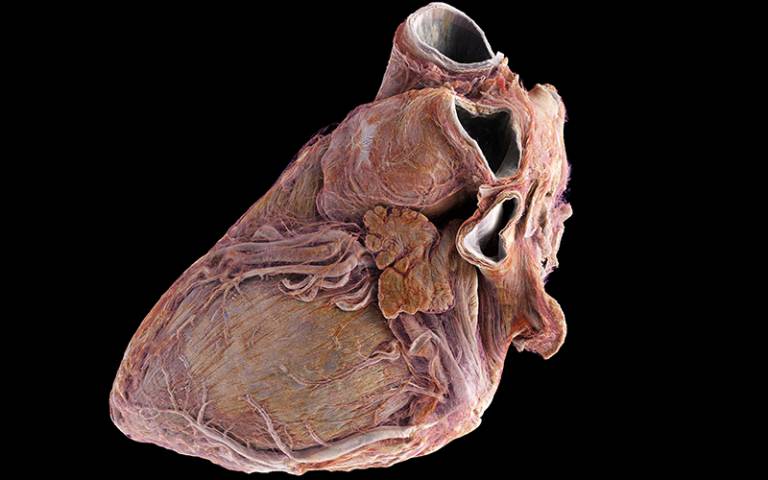

A zoom into the heart

UCL Faculty of Engineering Sciences

Rendering of the healthy heart. Credit: Siemens Healthineers 2024; Data UCL led ESRF Beamtime 1290.

Rendering of the healthy heart. Credit: Siemens Healthineers 2024; Data UCL led ESRF Beamtime 1290.

Research led by UCL in collaboration with the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) has developed an ultra-detailed atlas of the human heart using advanced imaging techniques.

Dubbed "Google Earth for the human heart," the atlas captures the entire organ's structure down to 20 micrometres, providing unprecedented insight into both healthy and diseased hearts. Using a technique called Hierarchical Phase-Contrast Tomography (HiP-CT), the team imaged two adult hearts, one healthy and one diseased, creating a 3D view 25 times more detailed than a clinical CT scan.

This transformative development enables research that was previously impossible, with applications ranging from better arrhythmia treatments to enhanced surgical models and new tools for diagnosis and treatment.

“With today’s technology, an accurate interpretation of the anatomy underlying conditions such as arrhythmia is very difficult. So, there is enormous potential to inspire new treatments using the imaging technique that we’ve demonstrated here,’ said Professor Andrew Cook (UCL Institute of Cardiovascular Science). “We believe that our findings will help researchers understand the onset of cardiac rhythm abnormalities and the efficacy of ablation strategies to cure them.”

The project contributes to the Human Organ Atlas, a global effort to create an open-access image database of human organs in health and disease, and was funded by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI).

Read the full story: ‘Google Earth for the human heart’ set to accelerate cardiovascular medicine

Internet addiction changes the brain

UCL Faculty of Population Health Sciences

People using smartphones. Credit: monkeybusinessimages on iStock

People using smartphones. Credit: monkeybusinessimages on iStock

A study of more than 200 young people with a formal diagnosis of internet addiction has found a link to behavioural changes and addictive tendencies.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) of multiple neural networks showed a combination of increased and decreased activity when participants were resting and an overall decrease in the functional connectivity in parts of the brain required for active thinking.

“The findings from our study show that this can lead to potentially negative behavioural and developmental changes that could impact the lives of adolescents,” said lead author Max Chang (UCL Great Ormond Street Institute for Child Health). “For example, they may struggle to maintain relationships and social activities, lie about online activity and experience irregular eating and disrupted sleep.”

Previous research has shown that people in the UK spend an average of more than 24 hours every week online and, of those surveyed, more than half self-reported internet addiction.

Read the full story: Internet addiction affects the behaviour and development of adolescents

Preventing extinction

UCL Faculty of Life Sciences

Critically Endangered Arabian leopard in Oman. Credit: Dr Hadi Al Hikmani

An artist in studio at the Slade School of Fine Art.

New research involving UCL could make a substantial contribution to averting extinction of the Critically Endangered wild populations of Arabian leopards, the region’s last remaining big cat.

By deploying camera traps across the Dhofar mountain range of Southern Oman, the research team were able to estimate that there could be only 51 wild leopards remaining in the country.

DNA analysis of scat samples showed that these wild leopards have extremely low levels of genetic diversity. “This is primarily due to the targeted killing of leopards in the 20th century, which led to in-breeding within smaller and smaller populations,” explained Dr Jim Labisko, UCL Centre for Biodiversity and Environment Research.

However, the team discovered higher levels of genetic diversity in captive leopards across the region, particularly among those from neighbouring Yemen. Their research proposed a plan for ‘genetic rescue’ through the introduction of offspring from captive-bred leopards into the wild population.

Both the findings and the methodologies used could help develop approaches for other threatened species.

Read the full story: Genes provide hope for the survival of Arabia’s last big cat

Climate anxiety

UCL Faculty of Education and Society

Credit: Gorodenkoff on iStock

Credit: Gorodenkoff on iStock

A UCL study reveals that girls are more likely to worry about climate change than boys and engage more with teaching on the topic.

The research team surveyed over 2,400 students aged 11-14 in England on their perceptions of both climate change and sustainability education.

53% of respondents indicated that climate change made them feel anxious and just 16% felt that adults are doing enough to protect the environment. Girls reported significantly higher levels of worry, with 44% expressing significant worry, compared to 27% of boys. Three quarters of girls wanted to learn about how climate change impacts health and wellbeing, compared to 60% of boys.

“Our report recommends embedding a more holistic education on climate and sustainability across the curriculum,” said Professor Nicola Walshe (UCL Centre for Climate Change and Sustainability Education). “We also suggest creating more opportunities for outdoor learning and student action on climate, and explicitly addressing students’ anxiety and fears.”

Read the full story: Girls more anxious about climate change than boys

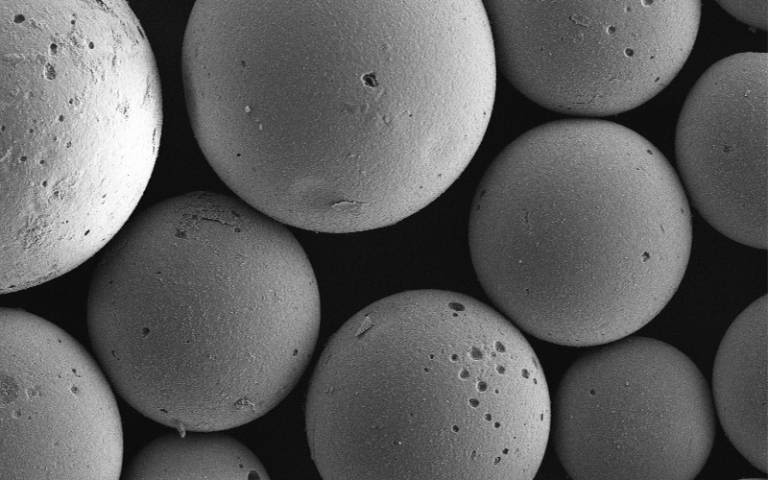

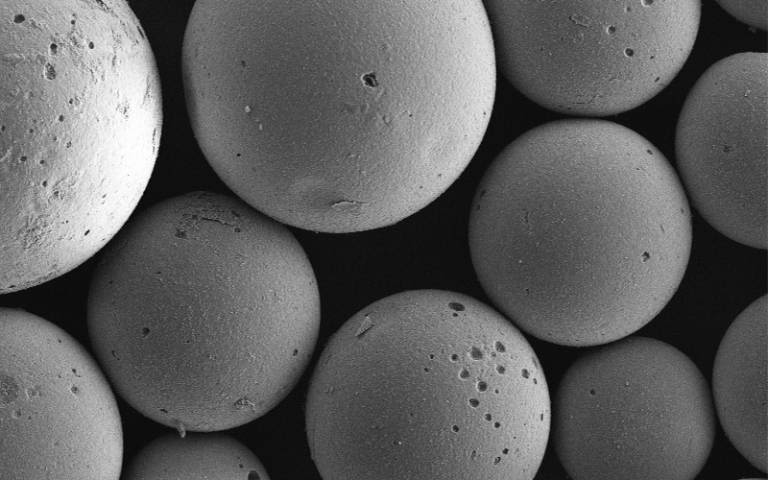

Beads versus bacteria

UCL Faculty of Medical Sciences

CARBALIVE beads viewed with a scanning electron microscope. Credit: University of Brighton/Yaqrit.

CARBALIVE beads viewed with a scanning electron microscope. Credit: University of Brighton/Yaqrit.

Tiny carbon beads developed by scientists at UCL and spinout company Yaqrit have been found to reduce bad bacteria and inflammation associated with liver cirrhosis and other serious health conditions.

The beads – known by the product name CARBALIVE – have a microscopic physical structure designed to absorb both large and small molecules in the gut. Ingested orally over several weeks, the beads were effective in preventing the progress of liver scarring and injury in animals with cirrhosis.

“The influence of the gut microbiome on health is only just beginning to be fully appreciated,” said senior author Professor Rajiv Jalan (UCL Institute for Liver and Digestive Health). “[This research] is exciting not just for the treatment of liver disease but potentially any health condition that is caused or exacerbated by a gut microbiome that doesn’t work as it should.”

The beads were also tested on 28 cirrhosis patients and proved to be safe with negligible side effects. If the same benefits are observed, the beads could be an important new tool to help tackle liver disease.

Read the full story: Carbon beads help restore healthy gut microbiome and reduce liver disease progression

Communicating lost pregnancies

UCL Faculty of Arts & Humanities

A patient and healthcare professional. Credit: fizkes (iStock)

A patient and healthcare professional. Credit: fizkes (iStock)

UCL researchers have conducted the first UK study to examine how language impacts the experience of pregnancy loss.

Feedback from 339 participants revealed that the terminology used in these contexts can significantly affect emotional well-being and recovery of those who have suffered pregnancy loss.

Participants found terms like ‘abortion,’ ‘termination,’ and ‘incompetent cervix’ particularly distressing, exacerbating feelings of guilt or self-blame.

“These findings really show just how important language is in pregnancy loss care, and the testimony of those who took part in the study illustrates the long-term impact it can have on someone experiencing pregnancy loss,’’ said lead author Dr Beth Malory (UCL English Language and Literature).

The study urges healthcare practitioners to consider the emotional impact of their language and calls for a shift towards more compassionate and personalised communication in pregnancy loss care.

Read the full story: Clinical language describing pregnancy loss can actively contribute to grief and trauma

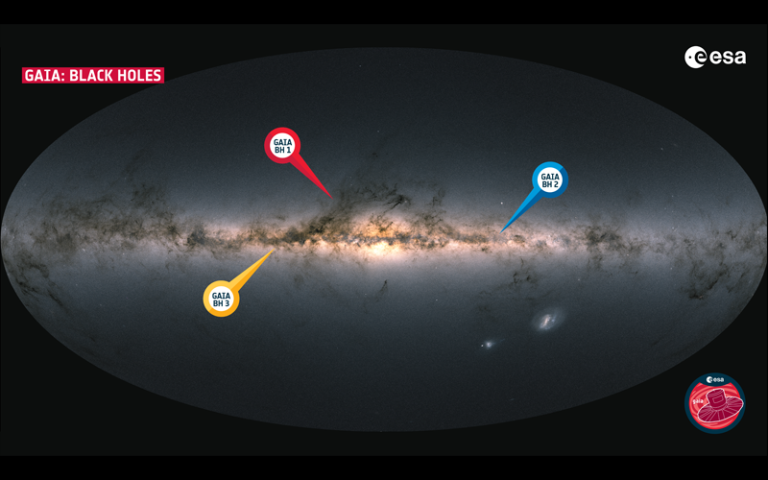

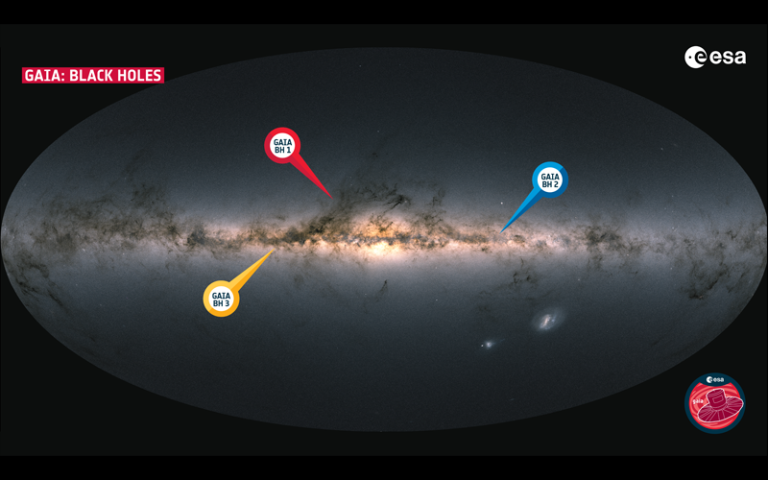

Hidden giants

UCL Faculty of Mathematical & Physical Sciences

Credits: ESA/Gaia/DPAC

Credits: ESA/Gaia/DPAC

The European Space Agency’s Gaia mission involving UCL researchers has discovered a massive dormant black hole called Gaia BH3, located 2,000 light years from Earth.

It is 33 times the mass of our Sun, making it the largest stellar-mass black hole found in our galaxy to date, and the first indisputable proof that black holes of this magnitude do exist.

Most of the 50 confirmed or suspected black holes in our galaxy are active – that is, they consume matter from a nearby star companion that is gravitationally bound to it.

Gaia BH3 does not have a companion close enough to steal matter from and therefore does not generate any light, making it very difficult to detect. The research team discovered it by inferring its position using the movements of what was previously considered to be a lone star, and is now understood to be the black hole’s companion.

“Finding Gaia BH3 enables us to start seeing our galaxy’s previously hidden population of dormant stellar black holes,” said Dr George Seabroke (UCL Mullard Space Science Laboratory). “Gaia’s next data release is expected to contain many more, which should help us understand how these black holes form.”

Read the full story: Large dormant black hole spotted in our galaxy

Justice for blood scandal victims

UCL Faculty of Laws

Sir Jonathan Montgomery, Professor of Healthcare Law at UCL, has played a significant role in shaping the UK Government’s comprehensive compensation scheme for victims of the infected blood scandal.

The scandal is one of most devastating in the history of the NHS, with over 30,000 people unknowingly infected with HIV and hepatitis C through contaminated blood products between the 1970s and 1990s.

As Chair of The Infected Blood Expert Group, Professor Montgomery has provided advice on how financial redress should be administered to those affected, covering awards for injury, social impact, autonomy, care costs and financial loss.

The Expert Group’s recent report indicated that family and carers who were not themselves infected but whose lives were impacted by wrongful infections will also be entitled to awards.

These recommendations will enable the new Infected Blood Compensation Authority (IBCA) to calculate awards promptly and without disproportionate requests for complex or inaccessible evidence.

Read the full story: UCL Laws Professor supports development of Infected Blood compensation scheme

Portico magazine features stories for and from the UCL community. If you have a story to tell or feedback to share, contact advancement@ucl.ac.uk

Editor: Lauren Cain

Editorial team: Ray Antwi, Laili Kwok, Harry Latter, Bryony Merritt, Lucy Morrish, Alex Norton