Food for thought

Discover how research from academics across UCL is shaping how and what we eat

Commercially driven disease

Dr Chris van Tulleken, author of best-selling book Ultra-Processed People and Associate Professor of Infection and Immunity at UCL, on the small changes to Britain’s food system that would significantly improve our health

When I started my career as a young infection doctor, I spent a lot of time in developing countries in Central Africa and South Asia. I saw many children die of infections, but not because we lacked antibiotics. They died because their parents were feeding them diluted baby foods that had been made up in unclean containers. They were diluted because they were largely unaffordable, and the formulas had also caused many parents to stop breastfeeding, which is so important for saving life in low-income countries.

These baby food products were being marketed in those countries completely inappropriately, and in some cases illegally, by the same companies that produce foods that make up a significant portion of our diet in the UK.

Seeing this firsthand made me interested in understanding the big structural things that shape human health. I made several TV programmes advising people on how to lose weight and live healthy lives. But on these shows I realised that the people I gave advice to were not able to follow it. And the same thing happens in the clinic. You tell people what to do and they don’t do it.

All my broadcasting, my research and my clinical practice became about asking “why can’t my patients change?” And “what are the major forces that control their lives?”

Food was the entry point to this.

When I began researching for Ultra-Processed People, the primary goal was to reduce the shame and stigma associated with diet-related disease, especially obesity. It was about trying to show that although more than half of us live with excess weight and almost a third of us live with obesity, it is not people's fault. It's not because they don’t understand the advice, or they are lazy or weak willed. It's because they are marketed foods that are engineered to drive excess consumption and weight gain. It’s about showing that diet-related disease is commercially determined.

Any solution to this must acknowledge that these problems are commercially driven, and that industry regulation is required.

However, throughout the system there are egregious conflicts of interest that make regulation challenging. I contributed to a recent investigation revealing that 60% of the members of the government’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition, the main food regulator that determines what a healthy diet is, are funded by the food industry.

But it’s also the press. The Science Media Centre that gathers most of the quotations for science stories in the UK press is funded by Nestlé, Procter and Gamble and FoodDrinkEurope, which itself is funded by Coca-Cola. Many universities’ nutrition departments are funded by big food companies. Fortunately, this isn’t the case at UCL. The British Nutrition Foundation, the UK’s largest food charity, is funded mainly by the food industry. Their ‘Healthy Eating Week’ last year was sponsored by Coca-Cola. Every way in which we engage with food, diet and healthy eating is influenced by the people who make the most harmful foods.

In my opinion, if that government committee has one person on it that has a conflict of interest with the food industry, we will not see an improvement in rates of diet-related disease in the UK. It just won’t happen.

The only way we managed to reduce the incidence of lung cancer was to make it clear that the tobacco industry used these conflicts of interest to get a license to operate. We stopped them from advertising, we taxed them, we put warnings on the packaging. Yet people are still subjected to a deluge of largely warning-free marketing from these food companies from all angles, at all times. To be clear, poor diet is the leading cause of early death globally – more than smoking.

It will be interesting to see what the new government wants to achieve in this area. But it feels like the UK is behind other countries that are already taking a clear view that diets made up largely of pre-packaged industrial foods are harmful. Countries like Mexico, Argentina and Chile have already introduced specific and clear warning labels for harmful foods high in calories, saturated fats, sugar, salt and non-nutritive sweeteners. In doing so, 99% of ultra-processed foods (that is, industrially prepared foods you wouldn’t be able to recreate in your own kitchen) have been given this labelling.

In the face of a catastrophic health crisis that will continue to become a greater economic burden, these feel like relatively light-touch suggestions. We need to remove conflicts of interest, add more comprehensive warning labels to these foods, tax particularly harmful foods differently, sell them on different shelves in the supermarket, and not market them to children with cartoon characters on the boxes.

I am optimistic that these things can and will change in my lifetime.

Dr Chris van Tulleken is an infectious disease doctor at University College London Hospitals and Associate Professor of Infection and Immunity at UCL.

Fussy eaters

Professor Clare Llewellyn is studying twins to understand how genes and environment contribute to the development of fussy eating over the course of childhood

Food fussiness is the tendency to eat a small range of foods, due to pickiness about textures or tastes, or reluctance to try new foods. It’s a common challenge and source of anxiety for many parents and caregivers. It typically emerges in toddlerhood but can persist into adult life. Yet we don’t know much about why it develops, or what parents can do to help their children eat a wider range of foods. I have a longstanding interest in this area because I was a fussy eater until early adulthood!

In a collaborative project involving UCL, King’s College London, the University of Leeds and the University of Cambridge, we undertook the first longitudinal study of the relative contribution of genetic and environmental influences on fussy eating, across five timepoints spanning toddlerhood to early adolescence. We used data from the Gemini study, a UCL-led research project which has been following 2,402 families with twins since 2007. It’s the largest twin study ever set up to examine genetic and environmental influences on early growth and eating behaviour.

With over a decade of information on identical twins, who share 100% of their genes, and non-identical twins, who share around 50%, we were able to isolate the drivers behind this particular eating behaviour.

We assessed the twin cohort between 16 months and 12-13 years of age and found that food fussiness peaked around the age of seven and declined slightly after this. Average levels of food fussiness were also relatively consistent in this period, indicating that it is a not necessarily just a ‘phase’ but may in fact be a stable trait lasting from toddlerhood to early adolescence.

At every age, non-identical twin pairs were much less similar in their fussy eating than identical twin pairs were, indicating a strong genetic contribution to individual differences in fussy eating. In fact, we found that genetic differences in the population accounted for 60% of the variation in food fussiness at 16 months, rising to 74% and above between the ages of three and 13 years.

These findings indicate that individual differences in children's tendencies to be picky or adventurous with food are largely down to genetic differences, rather than different environmental experiences. Ultimately, fussy eating does not develop because of poor parenting. We hope that by beginning to understand fussy eating as largely innate, we can somewhat alleviate the blame or pressure parents often put upon themselves when their child refuses to eat certain sorts of foods, or anything at all.

But genes are not destiny! These findings do not mean fussy eating is fixed and there is nothing parents can do. Environmental factors do still play a supporting role. For example, practices like family mealtimes and offering a variety of foods were shown to a have a significant impact on food fussiness during toddlerhood. Interventions such as repeatedly exposing children to the same foods may be most effective in the very early years. However, as children age, individual personal experiences like peer influences start to become more significant.

In the future, we hope to expand this study so that it includes a more diverse range of households. The study sample has a large proportion of white British households of higher socio-economic backgrounds compared to the general population of England and Wales. We aim to focus more on non-western populations where food culture, parental feeding practices and food security may be different. We’re also researching new ways that parents can support their child to feel more confident about trying new foods or eating a wider range of foods.

I’m passionate about supporting parents in navigating the many challenges they face when feeding young children. I published a practical book on this topic called An Appetite for Life, which summarises the latest evidence and advice on nutrition and feeding during the early years.

Fussy eating tips:

If a child refuses to taste a food, try offering them a very small amount for 20 days in a row. Research shows that this reduces the ‘fear factor’ of the food and increases familiarity, making them more likely to eat it. You can also encourage them to eat a particular food by sharing it with them, saying how delicious it is and showing them it’s safe to eat. Use praise and non-food rewards (like a sticker), and avoid pressure or punishments, as this can often lead to them disliking certain foods even more. Of course, if parents are very concerned, I would recommend talking to a healthcare professional.

Clare Llewellyn is Professor of Psychology and Epidemiology at UCL, and co-leader of UCL-REACH (Research into Eating, Activity and Health) in the Department of Behavioural Science and Health. She is also director of the Gemini study.

Did you know?

UCL has long played a role in shaping Britain’s health.

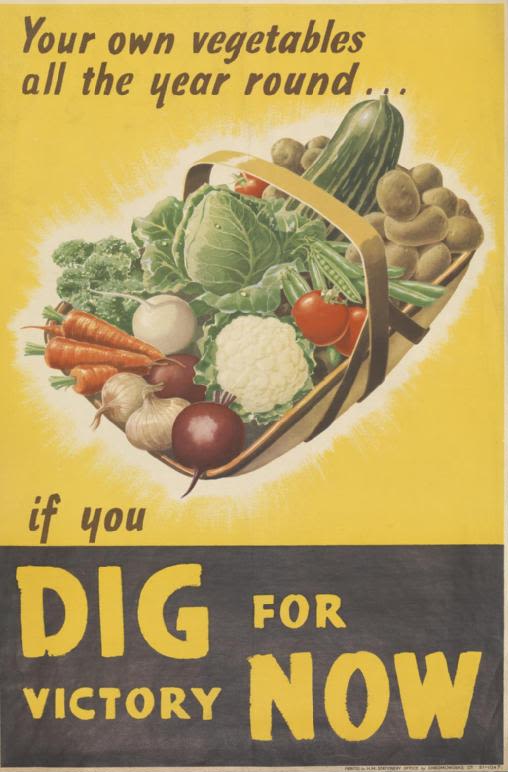

During the Second World War, Sir Jack Drummond, a biochemist and nutritionist at UCL, masterminded the national programme of rationing in Britain. He was appointed Scientific Advisor to the Ministry of Food in 1940 and produced a plan for the distribution of food based on “sound nutritional principles”. He advised on which foods should be prioritised and how to manage the food shortages in a way that would still meet the population’s dietary needs.

He saw rationing as an opportunity to combat what he called "dietetic ignorance" and believed that if successful, his system of rationing would not only maintain the nation's health but improve it. And he was correct.

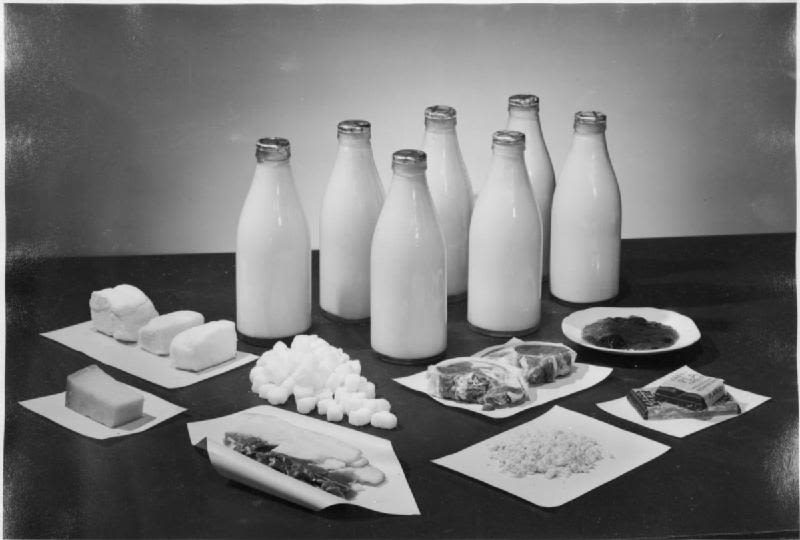

Rationing introduced more protein and vitamins to the diet of the poorest in the society, while the better off were forced to cut their consumption of meat, fats, sugar and eggs. He paid great attention to “protective foods”, like fruits, vegetables and dairy products that are rich in vitamins and nutrients. This led to the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign that encouraged people to grow their own vegetables.

Infant mortality rates declined and the average age at which people died from natural causes increased. Some still argue that the population’s general health has never been better than during rationing.

Drummond's contributions to wartime nutrition had a lasting impact on British food policy. His advocacy for better public understanding of nutrition helped lay the groundwork for post-war food and health initiatives, including school meal programmes and public education about the importance of a balanced diet. His scientific research on vitamins and nutrition continued to influence public health policy long after the war ended.

Today the Drummond Prize is awarded annually to the best second-year students in the UCL Biochemistry and Biochemistry-related BSc programmes.

Sir Jack Cecil Drummond

Sir Jack Cecil Drummond

A rationing pack for two adults for one week. There is milk, sugar, bacon, cheese, butter and chocolate. Other items were also rationed while bread, fruit, and vegetables were not. (Image: Imperial War Museums)

A rationing pack for two adults for one week. There is milk, sugar, bacon, cheese, butter and chocolate. Other items were also rationed while bread, fruit, and vegetables were not. (Image: Imperial War Museums)

Image: Imperial War Museums

Image: Imperial War Museums

Feed your brain

Dr Efstathia Papada is running a public engagement health initiative to improve the mental health of food bank users by supporting changes to their diet

Food insecurity, which often leads to inadequate diet, is growing in the UK. This is mirrored in the increased use of food banks, with more than 3 million people receiving emergency food parcels in 2023, compared to around 1.3 million in 2018 (The Trussell Trust, 2023).

In the same period, mental health disorders have become more prevalent, and research has indicated that poor mental health is rapidly increasing among adult users of food banks.

We launched the Feed your Brain project to increase awareness among users of food banks of the importance of balanced nutritional choices in supporting our mental health. When we consider the factors we can influence to improve our mental health, food and diet tend not to play a particularly significant role.

However, there is a growing body of evidence and almost universal acceptance among clinicians and academics, that healthy diet has significant benefits for our mental health. Positive associations have been found between sleep quality, balanced diets involving higher intake of vegetables, fruit, fish, water and fibre, and improved mental health. Numerous pathways have been identified through which diet could affect mental health, with special attention paid to certain nutrients like omega-3 fatty acids, or dietary patterns like the Mediterranean diet.

The UCL Nutrition team have longstanding relationships with several food banks and a food charity (FEAST With Us), and have been conducting research on the diet quality of food bank users. Our team made use of these links to collect information on the food parcels and services provided, the barriers around food provision, the support food banks offer and the needs of the users. We consulted the food bank users, members of staff and volunteers to be able to design and optimise activities that would be helpful.

First, we designed a pamphlet to allow service users to access information in their own time on how the food we eat is linked to our mental health. It includes recipes and easy, affordable tips for improving diet quality. It is now being distributed in food banks across London.

We also hosted pilot tasting sessions at the food banks, where users could try simple, nutritious and beneficial for mental health meals and take part in discussions on the topic of diet and mental wellbeing. Advice on small changes one can make was provided, such as:

- Consuming healthy sources of fat (such as olive oil, nuts, seeds, oily fish), whole grains, and fruits and vegetables that are rich in powerful nutrients.

- Including lean proteins like chicken or legumes in meals to help mood regulation.

- Eating enough fibre and foods with a probiotic effect, like yoghurt or kefir, to maintain a healthy gut – because our brain and gut are connected.

- Reducing sugar, caffeine and alcohol intake, as these can cause anxiety and poor sleep quality.

We received fantastic feedback from participants, who requested more initiatives like this in the future. We are now assessing the initial impact of our work and discussing how we can continue to extend the reach of this project.

Dr Efstathia Papada is a Lecturer in Nutrition at the UCL Division of Medicine and Programme Co-Lead for the MSc Dietetics programme.

From farm to table

Professor Aiduan Borrion is investigating the full life cycle impacts of meals to identify where food service providers can make the greatest improvements to the environmental cost of their meals

The global food system is the single biggest contributor to climate change, responsible for around one third of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions. We use half of the world’s habitable land for agriculture, predominantly for livestock, which is a major driver of biodiversity loss, deforestation, land degradation and pollution.

We are also faced with growing incidence of malnutrition and other diet-related diseases. This is partially explained by the progressive replacement of traditional diets by diets high in processed foods, refined sugars, harmful fats and oils, and animal products, which are also associated with higher environmental impacts.

Understandably we have seen growing interest in and demand for sustainable and healthy food options.

In 2018 we launched a project with the long-term goal of creating a toolkit and database to enable food service providers to make informed decisions about both the environmental impact and nutritional value of the meals they offer.

To do this we needed access to an enormous amount of information. So we started with the UCL canteen to test if it was possible to collect the necessary data and build a consistent model by which to measure all meals fairly.

We adopted a life cycle assessment approach, examining different foods and ingredients at every stage of life: production, transport and distribution, storage and preparation, serving and consumption, and waste management. While it was enormously time consuming and challenging to record and measure every element of these processes, we were able to start to identify the stages at which the greatest improvements could be made to environmental impact.

We expanded the project to several local primary and secondary schools. After completing further assessments on the lunches they served to pupils, it became increasingly clear that the most important factor in environmental cost was how ingredients are produced, often accounting for 65% (or more) of all environmental impacts examined.

Comparatively, things like transport played a limited role in the overall environmental cost of a meal, at around 6%. Local doesn’t necessarily mean more sustainable. For example, tomatoes from farms in the UK are often grown in heated greenhouses, and consequently can have a higher carbon footprint than tomatoes shipped from the other side of the world.

Then we compared meat-based meals against vegetarian and vegan meal options. Vegan meals consistently had the lowest environmental impact; 14 times lower than meat-based meals and three times lower than vegetarian meals.

Vegan meals did tend to have the lowest nutritional value, however they would always meet or exceed the minimum nutritional guidelines. This trade-off makes it complicated to make recommendations, but by collecting more and more data, we can enable food providers to make more informed decisions about their offerings.

The results thus far indicate that meal providers can reduce the negative impacts from production most significantly by changing menus to focus on procuring ingredients from integrated and organic production systems with good environmental standards. Replacing meat and animal-based ingredients with plant-based ingredients is one of the most impactful environmental interventions. Changes to food storage, preparation and waste management will help reduce negative environmental impacts but have significantly lower improvement potential.

It is clear that we need to be incentivising more sustainable farming practices. And for consumers, we need to be providing people with more information about how their produce is grown if they are to be able to make decisions about the environmental impact of their food.

Professor Aiduan Borrion is a Professor of Environmental Engineering and Co-Director of the Circular Economy Lab (CircEL) at UCL.

Alumni perspective

Lincoln Lee, UCL Biomedical Sciences alumnus (2019) and co-founder of Paddi, shares his experience of building sustainable supply chains for rice from Southeast Asia

While at UCL in 2018, my friend and I created a social impact rice brand as part of a university entrepreneurship programme. That same year we won the global Hult Prize, which challenges young people to solve the world’s most pressing challenges and awards the winner $1M in funding to make their business idea a reality.

We wanted to tackle a problem that felt relevant to our culture and the more we discovered about global rice production, the more we wanted to look at solutions.

The problem:

- A majority of smallholder rice farmers in Southeast Asia are trapped in cycles of poverty

- Up to 30% of all rice grown is wasted

- Rice cultivation is a major contributor to climate change

Farmers in the region are often part of unfair supply chains. There can be up to a thousand smallholder farmers selling to one buyer (often a large company), which gives farmers little bargaining power and suppresses prices.

Many of these farmers will take out loans during the growing season to pay for seeds and synthetic fertilisers and pesticides. They then repay the loans after harvest, keeping them in a precarious loop.

This makes it difficult to invest in more modern tools. They rely on traditional methods which are laborious and inefficient, which in turn causes rice to be wasted.

Most rice is grown by flooding rice fields. This practice is responsible for around 10% of global man-made methane emissions, a major greenhouse gas, and uses enormous amounts of water. Yet there is little incentive for these farmers to adopt more sustainable practices.

Additionally, the use of synthetic fertilisers and pesticides cause great damage to soil biodiversity, making it less productive over time. Farmers therefore end up buying more and more fertiliser while their yield goes down. Eventually this can cause desertification and impact local food security.

The solution:

Since graduating, we have spent the last five years trying to build sustainable supply chains that improve yield, reduce waste and help lift farmers out of poverty.

By exporting high quality, sustainable rice from Southeast Asia to restaurants and catering companies in the UK, we have been able to reinvest profits in equipment and machinery for farmers.

We bought industrial rice dryers and made them accessible to smallholder farmers. This isolates a key part of the rice production process that causes waste because farmers will often dry their rice under the sun, where mould can grow, or animals and insects can access it.

The rice dryers speed up the process, give them rice of a higher quality and more of it to sell. The dryers are also powered by rice husks, a waste product of milling the rice.

Now we are looking to complete the sustainable supply chain by supporting farmers to adopt more sustainable practices. Sustainable farming is usually harder work, so we are trying to incentivise it by offering contracts ahead of time, before the harvest season. This gives more security and reduces reliance on loans.

We have also begun encouraging the use of biological, regenerative soil inputs in place of synthetic fertilisers, which improves soil health over time and can thereby improve crop yield. Again, the challenge is that moving away from synthetic inputs will initially lead to a lower yield while the soil health recovers.

In doing this we are breaking smallholder farmers out of unfair supply chains by connecting them to new markets and linking them more directly from farm to fork.

Portico magazine features stories for and from the UCL community. If you have a story to tell or feedback to share, contact advancement@ucl.ac.uk

Editor: Lauren Cain

Editorial team: Ray Antwi, Laili Kwok, Harry Latter, Bryony Merritt, Lucy Morrish, Alex Norton