Features | Portico Magazine | Autumn 2025

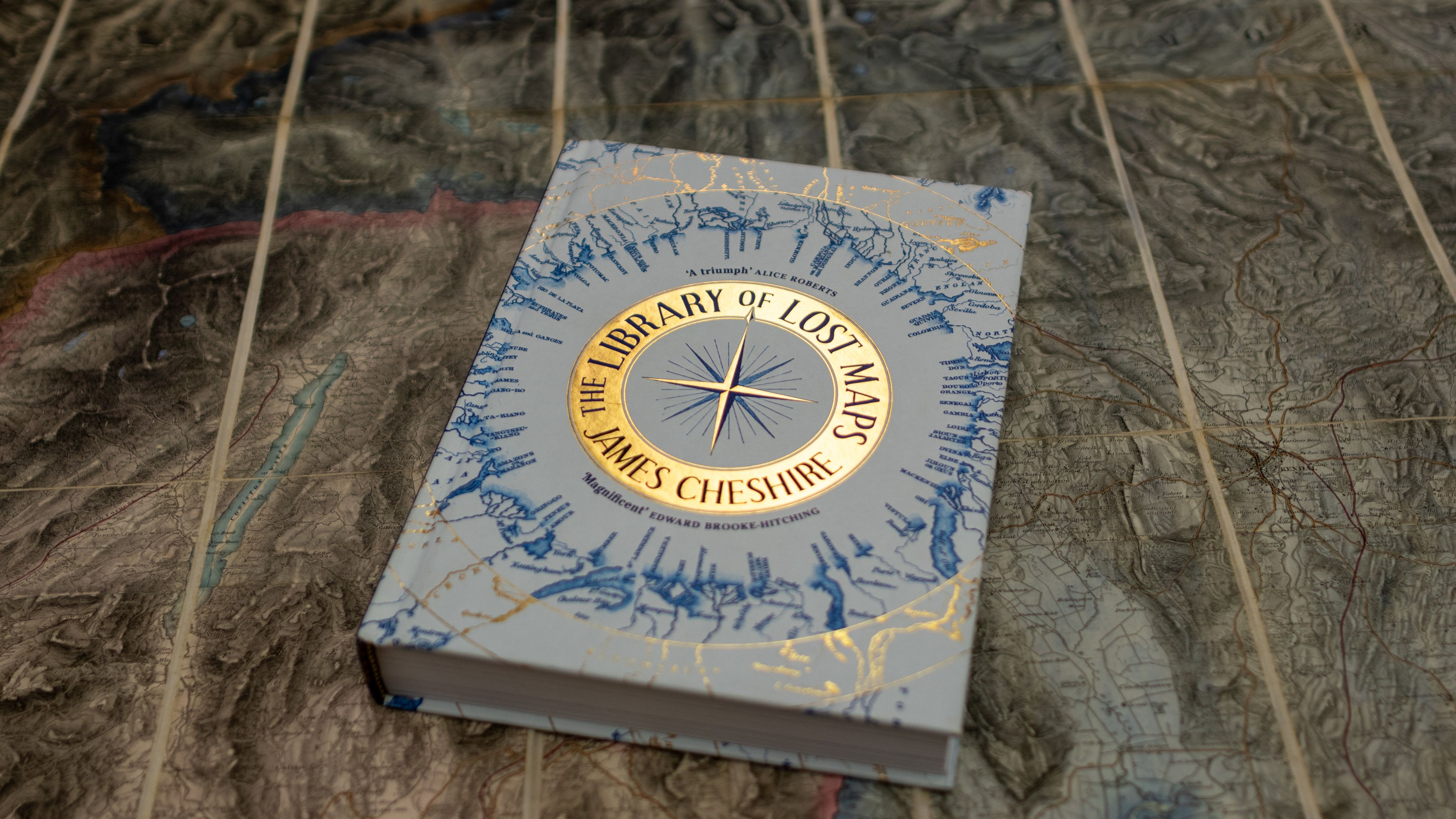

The Library of Lost Maps

UCL’s long-forgotten archive of maps reveals stories of war, science, empire and climate change, rediscovered through the eyes of a modern cartographer.

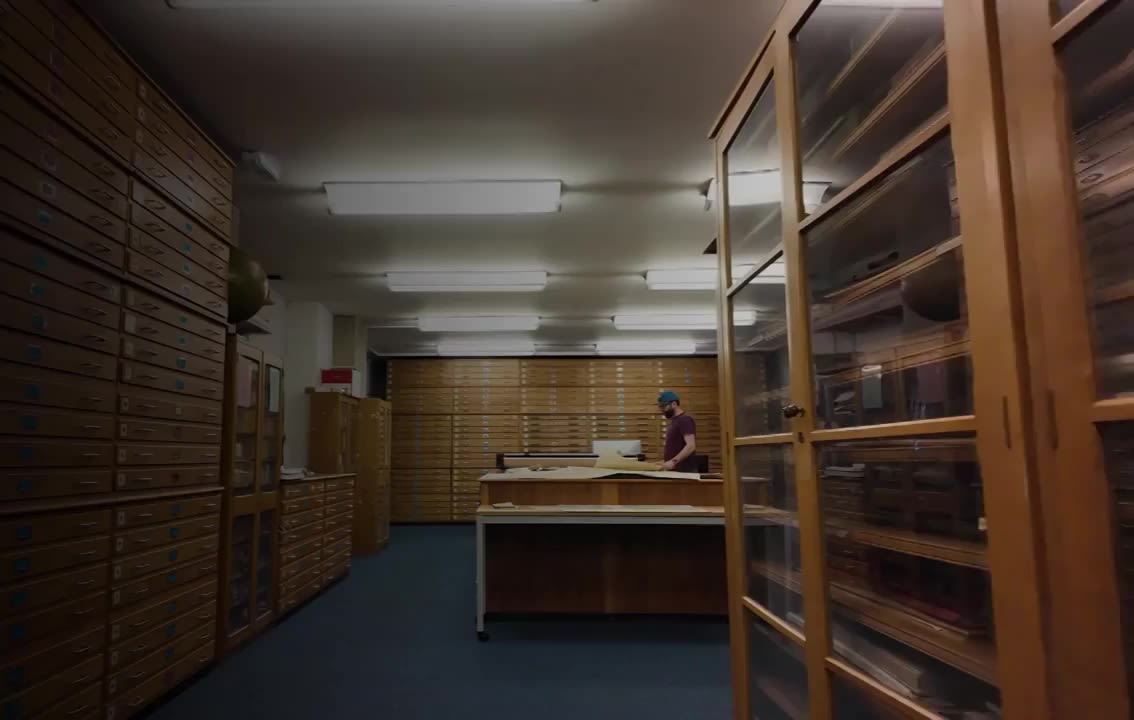

The UCL Department of Geography’s Map Library is full of surprises. So, when I excitedly opened each of its 440 bespoke wooden drawers, I was never sure what I might find.

Late one evening, I tugged at the handle of an unmarked drawer close to the floor and was disappointed to see what I thought was a decorator's dust sheet. It was thick with grime, but I noticed the word 'China' faintly scrawled in pencil across it.

Intrigued, I placed it on the large table in the centre of the room and began to carefully unfold it.

Map of China

The Northern Trading Company and Mr V.F. Yao-Hsuin (1931)

With each unfurling, more and more of a vast illustrated wall map of China came into view. Printed in the 1930s, it used astonishing illustrations to show everything from cities and regions to trade links, terrain, climate, culture, wildlife and more.

Captivated by the vividness of the map’s colours, which were in such sharp contrast to its folded exterior, I spent an hour marvelling at not just the cartographic skill but also the expense required to create it.

This ‘dust sheet’ was an early glimpse into this long-forgotten Map Library and one that started me on the journey of sifting through tens of thousands of maps, with many emerging to be the significant maps and atlases of the past two centuries.

To document the finds I wrote the book The Library of Lost Maps, which details the story - so far - of UCL’s unique, extraordinary, but little-known map collection.

Hidden in

plain sight

I joined UCL in 2008 as a PhD student and have risen through the ranks to become a Professor of Geographic Information and Cartography, and Director of the UCL Social Data Institute.

My teaching and research seek to inform the way data and mapping can innovate the social sciences, and for most of my time at UCL, I have been aware the collection of maps housed on the lower ground floor of the Brutalist architectural icon that is the UCL Institute of Education building on Bedford Way.

But it never occurred to me to open any of the drawers to see what they held. My focus has been on the future of mapping - paper maps, to me, felt antiquated and irrelevant.

Collins’ Standard Map of London

Edward Stanford Ltd (1869)

It wasn’t until one of UCL’s emeritus professors suggested making use of the space for my teaching that I began to understand the value of what we had. So once we returned to campus after the pandemic, I taught classes in the room. My students loved exploring its contents and handling the paper maps to appreciate their wildly different sizes and levels of detail.

It wasn’t until one of UCL’s emeritus professors suggested making use of the space for my teaching that I began to understand the value of what we had. So once we returned to campus after the pandemic, I taught classes in the room. My students loved exploring its contents and handling the paper maps to appreciate their wildly different sizes and levels of detail.

Il Cervino E Il Monte Rosa

Touring Club Italiano, Milano (1928)

It soon became clear to me that maps can also recalibrate our understanding across generations. For example, maps of glaciated regions evidence the climate-crisis induced retreat of their ice.

In The Library of Lost Maps, I show how the border between Italy and Switzerland has been redrawn to account for the changed landscape, as new ridgelines emerge from beneath the shrinking ice sheets that blanket the region surrounding the Matterhorn. The logic of the original border is clear from a historic map, which has become a reminder of the way that terrain can define nations.

I have long taught my students that maps reveal stories of colonisation, war, climate change and urban development and the Map Library had no shortage of these. But I was surprised to make discoveries that date from the founding of UCL and that surfaced unfamiliar stories about UCL’s role in shaping science, politics, and education.

UCL's role in

mapping history

A find that most strongly evokes UCL’s rich cartographic history was a bundle of maps I pulled from the back of a cabinet of atlases. It was an unpromising discovery, wrapped in torn brown paper and coated in black dust, but it turned out to be a pile of maps that coalesced into one of the most successful mapping projects of the 19th century.

They were produced by the fantastically named “Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge” (SDUK), an organisation that shared many founders with UCL, not least Henry Brougham who was a founder of both institutions in 1826.

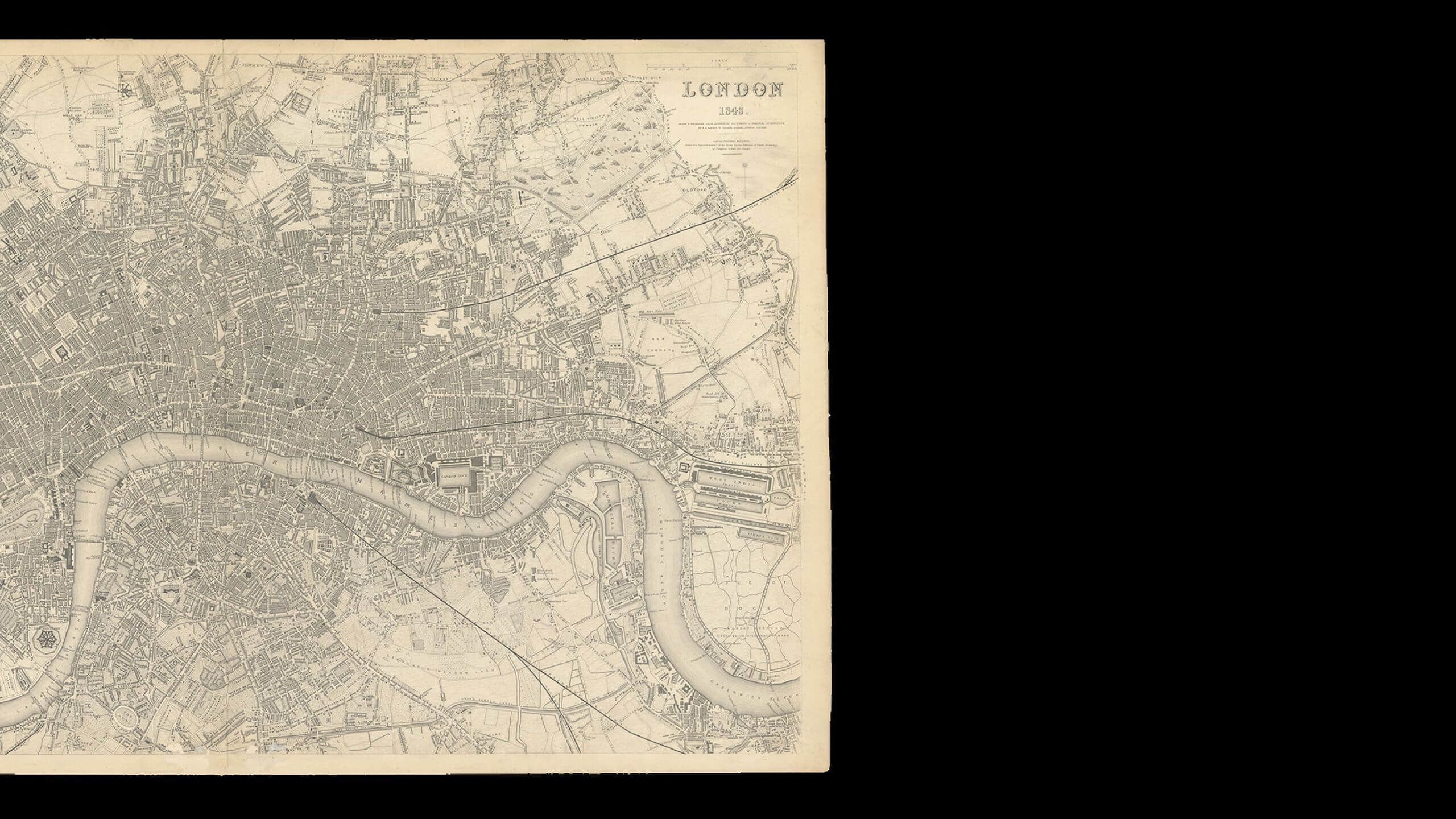

London 1843

Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (1843)

The SDUK, in line with UCL’s founding values, existed to democratise access to knowledge and bring education to those that would have formerly been excluded – particularly the rapidly expanding reading public. They quickly decided that geographical knowledge was ‘useful knowledge’ and that maps were essential educational tools and set about disseminating them well beyond society’s elites, who were the only people who could afford them at the time.

For a small monthly fee, readers would receive printed sheet maps, from Ancient Greece to the Americas, the Indian subcontinent to major European cities.

Between 1826 and 1848, they sold over three million maps. The maps were not just affordable but, because the SDUK invested heavily in the topographical research and engraving the steel plates used to print them, they were also incredibly high-quality. Many were printed within a few hundred metres of where UCL’s map library now stands. The plates were later sold onto other map publishers and there is even an SDUK branded globe in the Library of Congress that was taken from the office of Theodore Roosevelt.

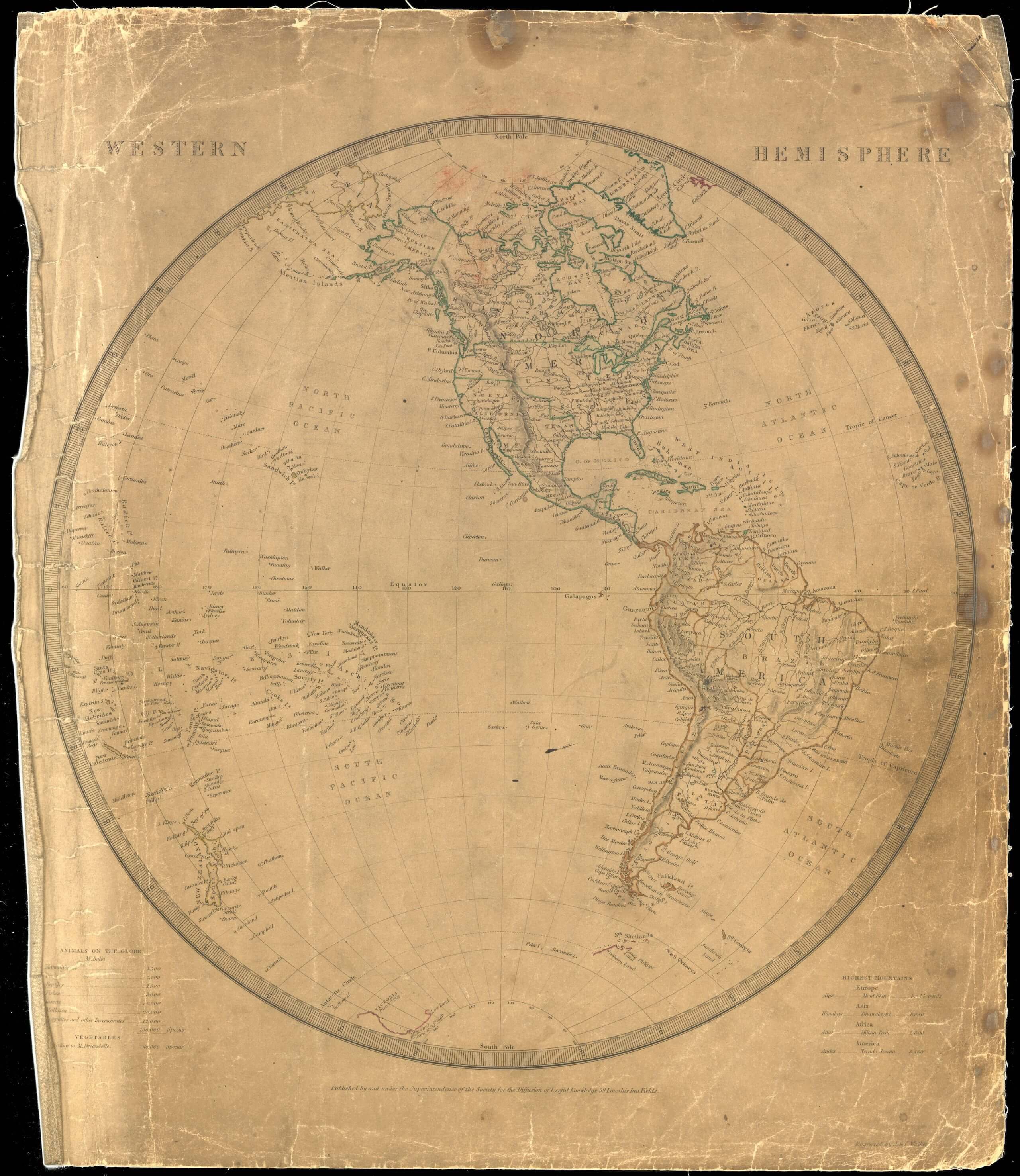

Western Hemisphere

Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (1844)

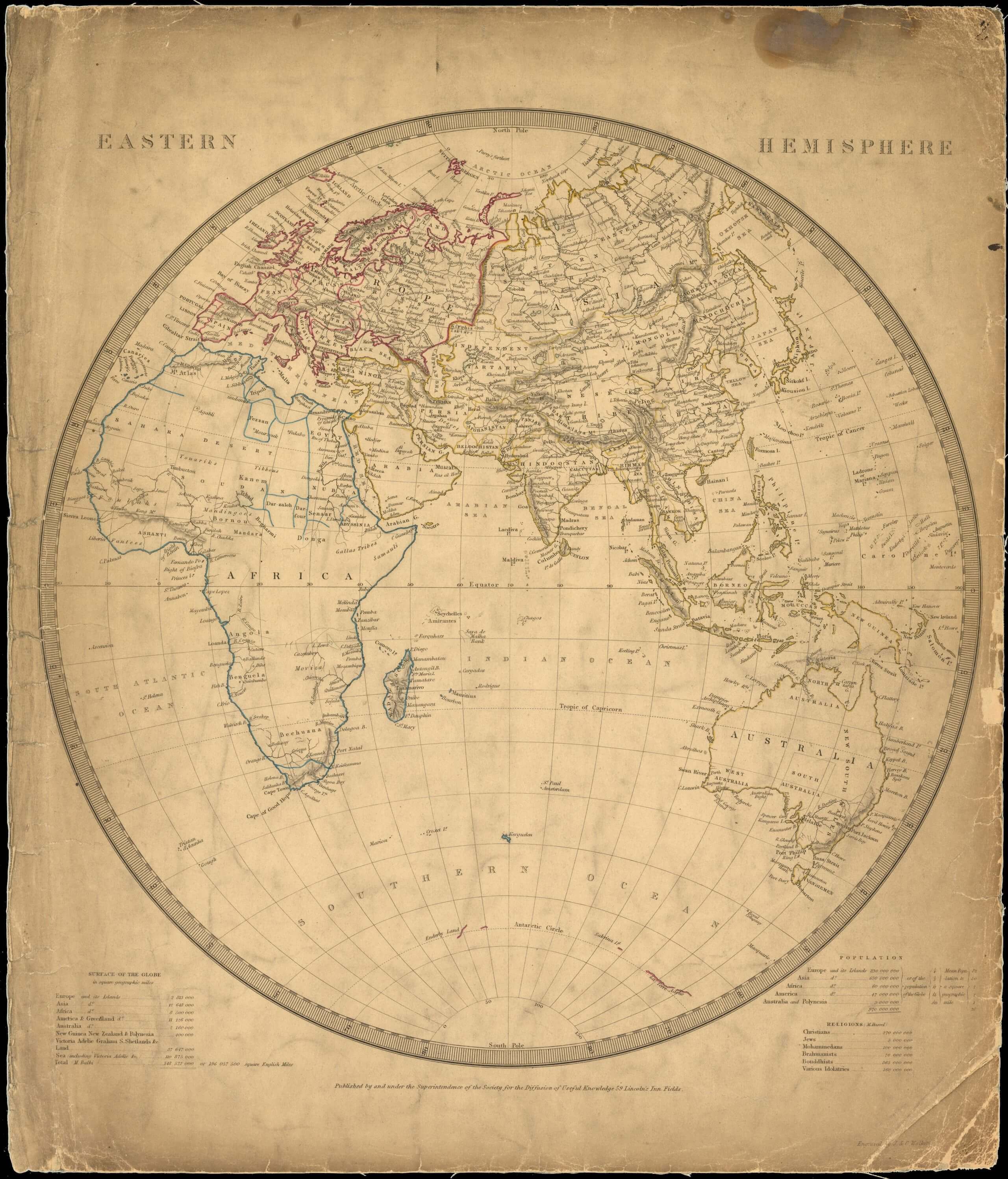

Eastern Hemisphere

Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (1844)

The quest for “useful knowledge” was enthusiastically pursued by the intellectual circles that surrounded UCL at the time of its foundation. One of the wealthiest and influential, but now overlooked, figures in this history is George Bellas Greenough, who made significant contributions to geography, geology and cartographic practices in 19th-century Britain.

A Geological Map of England and Wales

The Geological Society (1839)

He is best known for creating one of the first geological maps of England and Wales, published in 1820, which used new data and an innovative colouring system to highlight deposits of different types of rocks and minerals. It was ground-breaking in the way it displayed the resources that were lying under the ground, not just for those with an academic interest, but also for those who stood to benefit financially. At the time, raw materials were in high demand for fuelling the industrial revolution.

General Sketch of the Physical and Geological Features of India

G.B. Greenough (1854)

Greenough also produced the first geological map of the Indian subcontinent, despite never stepping foot in the region. Much as he had done for his earlier maps of England and Wales, he compiled the map from a systematic data gathering exercise that relied on correspondence with mostly colonial observers who were familiar with the local terrain.

Only thirty or so original copies of this map are thought to have survived, but I was delighted to discover another in the “India” drawer of the Map Library.

Here are the original hand-coloured sheets produced in 1855.

The Map Library also documents how, later, UCL geographers were involved in producing maps for the Paris Peace Conference at the end of the First World War and for military intelligence roles during the Second World War where they created maps that, for example, informed RAF bombing policy. In the 1970s, a former RAF pilot called Roger Tomlinson came to UCL and completed the first ever PhD in Geographic Information Systems, which is foundational to the electronic maps we take for granted today.

I feel privileged to have unearthed this time capsule of global events that UCL academics were part of. I hope that I can continue to preserve UCL’s maps, and that they will continue to inspire curiosity for students, researchers, and anyone who opens a drawer and sees the world unfold before them.

James Cheshire

Many of the maps in the UCL Geography Map Library require careful preservation and stabilisation to ensure they can be studied and enjoyed without risk of damage. With your support, we can safeguard them for future generations, ensuring the maps remain accessible for learning, research, and inspiration for years to come.

I feel privileged to have unearthed this time capsule of global events that UCL academics were part of. I hope that I can continue to preserve UCL’s maps, and that they will continue to inspire curiosity for students, researchers, and anyone who opens a drawer and sees the world unfold before them.

James Cheshire

Many of the maps in the UCL Geography Map Library require careful preservation and stabilisation to ensure they can be studied and enjoyed without risk of damage. With your support, we can safeguard them for future generations, ensuring the maps remain accessible for learning, research, and inspiration for years to come.

Portico magazine features stories for and from the UCL community. If you have a story to tell or feedback to share, contact advancement@ucl.ac.uk

Editor: Lauren Cain

Editorial team: Ray Antwi, Rachel Henkels, Harry Latter, Bryony Merritt, Lucy Morrish, Alex Norton

Shorthand presentation: Harpoon Productions

Additional design support: Boyle&Perks